TORONTO -- A woman from British Columbia is the first person in North America to be diagnosed with H7N9 bird flu, after apparently contracting the virus while travelling in China earlier this month, Canadian health officials said Monday.

Her husband, who had been travelling with her, was also sick with an influenza-like illness around the same time and it's believed he too was infected, but test results are still pending, said Dr. Bonnie Henry, B.C.'s deputy provincial health officer.

"We're quite confident he had the same thing," Henry said in a telephone interview.

The discovery of the case was announced Monday by Federal Health Minister Rona Ambrose, B.C. health authorities and officials of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

All stressed that it is unlikely more cases will result from this imported infection. To date there have been very few instances where H7N9 is believed to have spread from person to person. And there have been no reported illnesses among people who had contact with the couple when they were ill.

"All of them so far are well, including the ones that had the closest contact in the period early on in their infection," Henry said.

The couple, who are in their 50s, did not require hospitalization, but they were sick enough that they stayed home and had little outside contact at the height of their illness.

"It was very classic influenza. Fever and a cough," said Dr. Reka Gustafson, medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health.

"Though one of the individuals we interviewed said that it did feel a little bit different. That's probably about as close as she could describe it. And it felt different enough for her to seek care."

The couple's names were not released and officials would only say that they were residents of B.C.'s Lower Mainland region. They have since recovered.

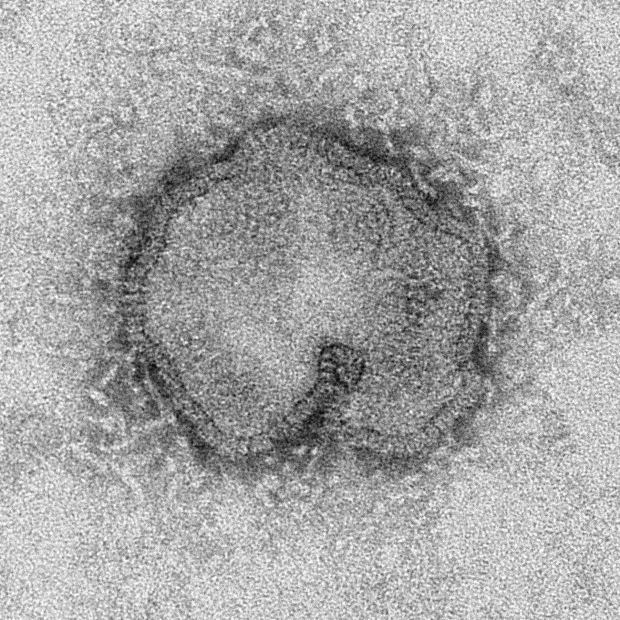

H7N9 is a subtype of flu that infects poultry. But in March 2013, authorities in China reported several cases of human infections. Since then, roughly 500 human infections have been diagnosed, all either in China or in people who had travelled to Mainland China. Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia have all diagnosed infections in returning travellers.

Roughly a third of the known infected patients died from the infection. The death rate is lower than that of the other main bird flu virus that sometimes infects people, H5N1, which kills just under 60 per cent of the people who become infected.

Despite the fact it isn't as deadly, flu experts consider H7N9 to be at least as worrisome as H5N1.

For one thing, H7N9 seems to infect people more easily. There have been 500 H7N9 infections in less than two years; the cumulative count of H5N1 cases is about 700, but those infections have built up over more than a decade.

And H7N9 doesn't make poultry visibly ill, which means it's impossible to know which chickens are infected. H5N1 is lethal to poultry; dying chickens make outbreaks easy to spot.

This British Columbia H7N9 infection might easily have gone undetected but for the actions of an astute family physician.

The couple returned to Canada from China on Jan. 12. Two days later, the husband became ill with influenza-like symptoms. A day after, the wife developed the same symptoms, and decided to seek medical help.

"Typical behaviour -- he stayed home and she went to see her doctor," Henry said.

British Columbia -- like the rest of the country -- has been in the grips of a very active seasonal flu outbreak this month. The woman's doctor could easily have diagnosed influenza based on the woman's symptoms and sent her home to rest and recover.

Instead, the physician swabbed the woman's throat and sent the test to the provincial laboratory for testing.

The next day, when she received confirmation that her patient was infected with an influenza A virus, the doctor prescribed the flu drug oseltamivir -- sold under the brand name Tamiflu -- for the woman and her husband.

"I think it is surprising that we discovered them as cases," Henry admitted.

"If she had not done that test -- both of them recovered uneventfully, they were given Tamiflu by the family doctor -- we never would have known."

H7N9 is an influenza A virus. But so are H1N1 and H3N2, the flu virus responsible for this season's flu activity. Laboratories do not subtype every single positive flu test doctors submit during flu season; they process a representative sample. Had the lab stopped after this virus was identified as an influenza A, the assumption would have been that the woman was one of the many Canadians who was infected with H3N2 this winter.

But the lab -- the B.C. Centre for Disease Control -- tried to type the woman's sample, and discovered it was not a match for either H3N2 or H1N1. When further testing revealed it was an H7 virus, BCCDC alerted local and provincial public health officials, and the Public Health Agency of Canada was notified.

At that point public health officials reached out to the couple, and the man was tested. Results are still pending, but given that he had recovered it is likely the test will come back negative, Henry said. She added that there are plans to test blood samples from both the man and the woman for antibodies to the H7N9 virus.

Meanwhile, the woman's sample was flown to the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg for additional testing, which confirmed Monday that she was infected with H7N9, said Dr. Gregory Taylor, Canada's chief public health officer.

Taylor said Canada has informed the World Health Organization, as it is required to do under the International Health Regulations. And it is providing China with information on the cases.

But it appears unlikely that anyone will be able to determine precisely when and how the couple became infected. They reported being in a number of places where chickens were present, but that is common in China.

"There's a number of different periods of time where they were aware of there being birds around and bird droppings in a number of places. So we're going to give the details to the Chinese government obviously. But we're not going to say where because we can't tell where the exposures were," Henry said.

Last January, a woman from Red Deer, Alta., died of H5N1 bird flu, the first known case in North America. She too had recently returned from a trip to China, but officials couldn't determine how she became exposed to the virus.

"We never did find out exactly where that case came from and I would assume in this current one that we probably won't find out either," said Taylor. "It's extremely difficult to detect where that came from."

Taylor said the Public Health Agency does not recommend that Canadians travelling to China avoid particular cities or towns -- H7N9 has been found in many parts of that country -- but it does urge people to avoid contact with poultry and so-called wet markets, which sell and slaughter live poultry.