TORONTO -- The Crown's contention that three former Nortel executives orchestrated a widespread book-cooking scheme is a "fantastic conspiracy theory," a defence lawyer said in closing arguments at the high-profile trial that concluded Wednesday.

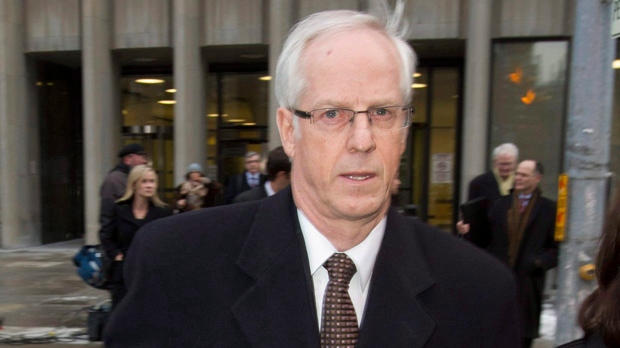

Greg Lafontaine, who represents the now defunct telecom giant's ex-CFO Douglas Beatty, said allegations that the top-ranking Nortel executives oversaw an accounting scandal at the firm -- which once had 90,000 global employees in numerous divisions -- is baseless.

"This is not a case of a small operation where one individual or another is going to have the leeway, going to have the rope, going to have the freedom to act irresponsibly, or on their own," Lafontaine told the court.

"It can't happen in the structure we heard about, at Nortel."

The Crown has alleged that Beatty, along with ex-CEO Frank Dunn, and ex-controller Michael Gollogly, tampered with accounting in 2002 and 2003 to trigger $12.8 million in bonus payments and stocks for themselves.

Those return-to-profitability bonuses were tied to internal targets that the Crown says were reached only by releasing accruals -- money set aside to cover future liabilities -- onto Nortel's balance sheets in quarters when it wanted to show it was turning a profit, when it was actually in the red.

The fate of the three men, each charged with two counts of fraud, is now in the hands of Ontario Superior Court Justice Frank Marrocco, who has reserved his decision until January 14, nearly a year after the proceedings began.

All three men, who were fired from Nortel in 2004, have pleaded not guilty. If convicted, each could face up to 10 years in prison.

Lafontaine told the court that the Crown presented no evidence about the involvement of countless accredited accountants from Nortel and outside auditors Deloitte & Touche working together to manipulate the books.

Instead, he accused the Crown of calling reputable witnesses "liars and purjurers" when testimony did not fit with their theory.

Dunn's lawyer David Porter said while his client approved all the accounting at the beleaguered telecom equipment maker during his time as chief executive, it would've been "impossible" for him to know whether the figures were accurate.

"He did not personally review all of the accounting before certifying," Porter said. "That is impossible."

Instead, Dunn trusted his company's accountants and auditors when they gave him financial statements to rubber stamp.

"He had no reason to doubt Nortel's accounting," said Porter.

Dunn's approval was symbolic and he shouldn't be held responsible if the numbers were wrong, according to the defence.

Porter told the court that the Crown has failed to show evidence that his client made "any attempt to rejig the (financial) targets" or instructed any of his employees to do so.

At the time of the alleged offences, Dunn was preoccupied with "desperately working to save a company" and not orchestrating a widespread white-collar crime ring, as the Crown has suggested.

"The company was struggling to stay alive," said Porter.

Nortel, which had been losing millions for years, was in flux during that period, with attempts to restructure by shedding a third of its 90,000-strong workforce and return to profitability.

Meanwhile, Gollogly's lawyer, Sharon Lavine, said her client had a reputation within the company of "getting the numbers right."

Collectively, the defence argued there was no fraud at Nortel, just their clients' unawareness of improper accrual policies that were known by Deloitte & Touche.

Yet the Crown has argued that the company's balance sheets were purposely manipulated and millions of dollars of reserves were held back so they could be reported in the early quarters to give the illusion that it was turning a profit.

In one example, the Crown said the board was told in March 2003 that Nortel was forecasting a loss but a month later, that figure had turned into a profit, even though the company was losing hundreds of millions for operational costs.

At the time, the Crown said the company had $189 million in excess accruals, but illegally released only $80 million to boost numbers during the first quarter of that year, while holding onto the rest for use in future quarters.

It's also alleged that a year earlier, Nortel's own accountants were aware of $303 million in cash reserves that were held for no legitimate reason.

The accounting scandal resulted in Nortel's stocks nosediving from a peak of $124.50 a share to penny-stock status in one of the largest financial downfalls of a Canadian company in history.

Nortel filed for bankruptcy in Canada and the U.S. in 2009 as the result of mounting losses, falling sales, big debts and a gamut of legal issues.

Thousands of Canadians lost their jobs when Nortel folded.