TORONTO - Dr. Markus Selzner has just come from surgery, still in his scrubs, and he's excited to show off his baby.

A configuration of fluid-filled tubing, pumps and other mechanical components, it's not the prettiest baby - but it's one Selzner and his team hope will one day revolutionize kidney transplants by boosting the number of available donor organs.

The “ex-vivo” machine, five years in development, preserves and rejuvenates less-than-ideal kidneys by mimicking the conditions inside the body prior to transplant.

Those could be kidneys from deceased extended-criteria donors who were over age 60, or from younger donors who had a condition such as high blood pressure or diabetes or had died from a stroke.

“The first thing we can do is to give the kidney an environment that is as close to the human body as possible,” said Selzner, a transplant surgeon at Toronto General Hospital.

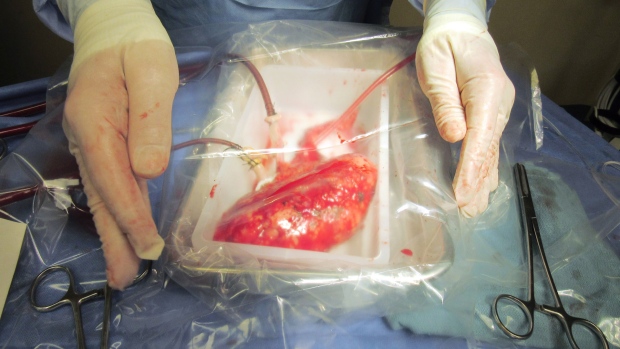

Through the renal artery, the machine pumps a mixture of oxygenated red blood cells, proteins, salts and glucose into the kidney as it nestles in a surgical tray, with all the components kept at body temperature of 37 C.

And just like the organs in the body, this so-called kidney-in-a-box secretes urine and other waste products, which doctors can measure along with other critical functions to determine the organ's health before implanting it into a recipient.

“That's the most important principle - the kidney should think it's still in the human body and it should work like it's in the human body,” said Selzner.

“The kidney system imitates this with a pump, which is like the heart. We give oxygen like the lungs and we give nutrition like the bowel would give,” he said, noting that the organ would be perfused for several hours.

Traditionally, transplant surgeons get offered a donor kidney from another hospital that's a tissue match for a patient on the waiting list.

The organ is transported on ice, at which point doctors on the receiving end physically assess the kidney. But they have little information on how well it will function once transplanted. Too often, they end up having to decline the organ, said Selzner.

As well, kidneys that have been cooled during transport can be “sleepy” and don't begin functioning for a day or more after transplant, leading to the recipient being kept on dialysis and in hospital longer. The transplant may have a shorter lifespan as well.

“And by taking this away, these organs should be champions,” Selzner said of kidneys given the ex-vivo treatment instead of cold-storage.

“They are not athletes at the end of the run, they are athletes like at the beginning of the run ... they will be strong, happy and fully loaded.”

In November, Selzner and his team implanted the first donor kidney rejuvenated through the system in a 53-year-old patient who had been on hours of daily dialysis.

“I feel great,” Zhao Xiao, a married father of two who works as a cook in a Toronto restaurant, said through an interpreter.

“This can make a difference to other patients, so I am glad to be the first one helping them with my experience.”

Nearly 80 per cent of the more than 4,500 Canadians on the waiting list for an organ transplant need a kidney, says the Kidney Foundation of Canada.

In Ontario, for instance, there are about 1,000 people needing a kidney transplant, with a typical wait time lasting roughly four years. About five per cent of patients die while on the waiting list every year.

“What we hope to achieve is getting more kidneys for our patients so they wait less on the waiting list and they have better kidneys,” said Selzner, adding that the goal is to expand the technology not only across Canada but around the world.

But revitalized donor kidneys are only part of the story.

In 2008, Drs. Shaf Keshavjee and Marcelo Cypel of Toronto General were the first in the world to pioneer the ex-vivo technique to help repair damaged donor lungs.

As a result, there's been a major increase in lung transplants at the hospital since 2012, and similar systems are now used worldwide. TGH alone has performed 308 lung transplants with ex-vivo-enhanced organs.

The technique has also been used to perk up less-than-premium donor livers, and researchers at the hospital are working to extend the principle to hearts.

“The whole idea of the ex-vivo preservation strategy is not so much just to be able to assess organs, which I think is an important short-term goal,” Keshavjee said.

“But really the idea is can we make better organs? Can we actually end up transplanting an organ that is better than the way that we found it?

“And certainly with lungs, where only 20 per cent of the donor lungs that are offered can be used safely, we've shown that with this technique we can double the number of lung transplants performed in the world with our new technology.”

That's only a start.

The researchers are working on using gene and stem cell therapies to help donor organs further repair themselves using the outside-the-body technique and to make them less subject to rejection by molecularly tweaking them for individual recipients.

“When you think of a vision of the future, you'll be seeing I think that almost all organs will end up going on support systems like this to maintain them until they're ready for transplant and to improve them and prepare them in a personalized way for each patient,” Keshavjee predicted.

“So we're developing a machine that will allow us to do 10 lungs at a time instead of one, and I think it will be the same for kidney and liver, and we're working on that,” he said.

He also envisions donor lungs, hearts, kidneys and livers being processed in organ repair centres, which would then transport them to “the right patient at the right time.”

“I don't think we'll be sending every organ in a Lear jet like we do today. I think we'll send organs by drones.”

While a ways in the future, there may even come a time when people won't need organ transplants.

Keshavjee believes the scientific work being done now will lay the groundwork for researchers building organs from scratch or being able to “repair your own lung inside you so that you don't need a transplant.”