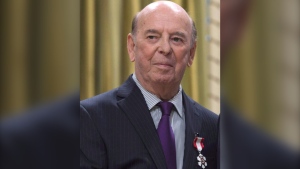

MONTREAL -- When Gaetan Barrette, health minister under the previous Liberal government, wanted to give nurses more authority, he said he had to personally intervene in the file and threaten Quebec's college of physicians.

"Behind closed doors I said: 'Either you move or I will legislate' -- and they moved," Barrette said in a recent interview. As a result of his efforts, nurse practitioners in the province gained the authority last March to initiate treatment for six chronic illnesses and to prescribe more medications than had previously been the case.

But patients are still required by law to be seen by a doctor within 30 days of being treated by a nurse practitioner. And unlike their counterparts in Ontario, Quebec's roughly 500 nurse practitioners -- also known as registered nurses -- are not allowed to make diagnoses on patients.

The province's new health minister, Danielle McCann, wants to change that. She said this week that doctors are ready to cede more room to nurses. By the end of the year, the minister said, Quebec's registered nurses could be diagnosing patients.

Barrette, however, who is now on the opposition benches, says McCann's comments are wishful thinking unless she is ready to use the legislative stick and force doctors to change their ways. "She will not get what she wants without legislating," he said.

Quebec's college of physicians did not return a request for comment, but in the past it has opposed giving nurses the authority to make diagnoses. Barrette, a radiologist who was president of the federation of Quebec's medical specialists from 2006-14, said there is a culture among Quebec doctors that makes it difficult for them to accept change.

"It's their profession, it's their fibre -- their essence," he said. Some doctors "who are rational," Barrette said, accept giving nurse practitioners the authority to make diagnoses -- but they are a minority.

"A doctor in Canada, on average, sees 30-35 patients a day," Barrette said. "In Quebec, it's 14. I did everything to change that, and it is changing. But there is more work to be done."

Barrette says the nursing profession is also partly to blame. "We are facing two organizations who are corporatist," he said. Each side wants to protect its own territory. Nurses want to have a parallel system alongside doctors, Barrette explained, while most doctors don't want change.

Prof. Yannick Melancon Laitre, nurse director at McGill University's primary care nurse practitioner program, said Quebec has been debating the authority of registered nurses since 2012. He said he is "always a bit skeptical" about whether nurses and doctors can agree to co-operate.

"I'm excited for us to just come to a decision -- to stop talking about it and arrive at a result that is similar to our colleagues in Ontario," he said in an interview. Registered nurses in Ontario have significantly more authority than in Quebec. They can diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests, and as of 2017, can even prescribe controlled substances such as opioids if they receive additional training.

Laitre says the differences between Quebec and Ontario nurses "seem trivial" but they are not, especially when it comes to insurance claims. The fact nurses in Quebec can't use the word "diagnosis" means the medical care they offer isn't covered by private insurance policies. Their work must be overseen by a doctor, which increases bureaucracy in the system, he said.

"We're doubling up on the services instead of working in collaboration with doctors," Laitre said.

Barrette said research has shown how to reduce waiting times and increase access to medical care. Doctors need to take on more patients, he said, and nurses and doctors should work together each with their own, clear authority. Unfortunately, he said, less than 20 per cent of doctors in Quebec work this way, he explained.

A 2015 government proposal that was eventually dropped because of a backlash from doctors would have required young doctors to be responsible for a minimum of 1,500 patients. Barrette argues that if clinics were properly organized, one doctor could be responsible for 3,000 patients.

"But in order to do that you need nurse technicians, auxiliary nurses, and nurse practitioners," he said. "You need all three. And it exists. But it needs to happen more."