TORONTO -- An Ontario judge erred in determining that the possible harm caused by solitary confinement could be managed by monitoring inmates and pulling them out of isolation if they appear unwell, a civil rights group argued Tuesday in challenging the ruling.

Lawyers for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association told a three-judge panel at Ontario's top court that knowingly exposing inmates to harm and then removing them after harm has occurred amounts to cruel and unusual punishment, which contravenes the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

"Every inmate who goes in is exposed to the real risk of serious harm," lawyer Jonathan Lisus said at the appeal court hearing. "Those who suffer harm, it is often permanent and severe," he said, citing paranoia, depression and suicidal ideation as lingering effects in some cases.

The association is arguing Ontario Superior Court Justice Frank Marrocco didn't go far enough in ruling that isolating inmates for more than five days in a practice known as administrative segregation is unconstitutional because the system lacks proper safeguards.

It is asking Ontario's top court to impose a 15-day cap on solitary confinement for inmates and to bar the practice altogether for youth and other vulnerable groups. When asked why it wasn't seeking to eliminate administrative segregation entirely, the association's lawyers said it may be needed in emergencies and a cap would reduce the exposure to harm.

"These prisoners haven't done anything," Lisus said. If the goal is to ensure their protection, there's no need to keep them locked up for 22 or 23 hours a day, he said.

Inmates are placed in administrative segregation to maintain security in the event an inmate poses a risk to themselves or others and no other reasonable alternative is available. They are to be released from administrative segregation at the earliest possible time.

The federal government said a provision in the law already requires that an inmate's health be taken into consideration when it comes to segregation. It said that includes mental health, though the association disagreed with that reading.

"As found by Associate Chief Justice Marrocco, the ongoing monitoring of inmates in administrative segregation -- which consists of daily visits by nurses charged with determining physical health care needs and/or risk of suicide or self-injury, and the assessment by a mental health professional at regular intervals throughout an inmate's placement -- is sufficient to identify when an inmate's health may be impacted," government lawyers wrote in their submissions.

"If there is such an impact, the legislation requires a balancing of the harm of continued placement in segregation against the benefits to safety and security in deciding whether to maintain or release an inmate from segregation."

The government lawyers further said the judge was correct in finding that just because corrections staff violated an inmate's charter rights in some cases, that didn't mean the law itself is unconstitutional.

The association argued the case was not one of maladministration. The purpose of administrative segregation, Lisus argued, is to "impose (and) sustain indefinite deprivation of meaningful human contact."

Last December, Marrocco gave the federal government a year to change its law to reflect his ruling, noting that doing so immediately could put inmates and staff at risk. The deadline is Dec. 18.

Ottawa is expected to request Wednesday that the appeal court grant a seven-month extension. The civil liberties association said it will oppose the motion.

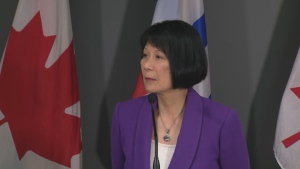

"The government was given a year to fix this, they didn't," Michael Bryant, the group's executive director, said outside court.

"Every day that goes by that this old, unconstitutional system is in place is a day that cruel and unusual punishment is happening in Canada."

Bryant added that the federal government only introduced legislation that deals with solitary confinement last month, meaning it will not pass in time to meet the deadline and may not do so before the next election.

He further said the bill doesn't address the findings of Ontario and British Columbia courts because it doesn't include independent review of placements, among other things.

"What they're doing with this legislation is far too little and way too late," he said.

A court in B.C. also struck down the federal law earlier this year but went further than the Ontario court, ruling that indefinite solitary confinement of prisoners is unconstitutional and causes permanent harm. That ruling also imposed a 12-month deadline for making changes.

The government is appealing in that case, saying it needs clarity because of the differences between the two rulings.

Those in segregation are restricted to two hours outside their cells and cannot interact with others or access programs.

In addition to administrative segregation, prisons can also employ disciplinary segregation, which is used to punish inmates for violating prison rules for a maximum of 30 days.