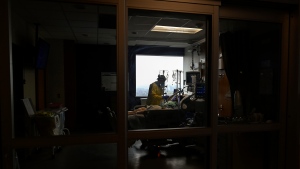

TORONTO - Intensive care nurse Jane Abas is assessing her patient, checking her medication and monitoring her heart rate.

The 68-year-old woman tested positive for a COVID-19 variant shortly after arriving at Toronto's Humber River Hospital for an unrelated health concern. Her condition rapidly deteriorated and she had to be placed on a ventilator, suffering a cardiac arrest after the intubation process.

Abas says the woman is more stable this morning, but as cases involving the variants of the novel coronavirus rise, a patient's situation can change quickly. The day before, another COVID-19 patient in a similar condition - who had just retired last month - passed away. She says it happened fast.

“We tried to bring them back, we couldn't,” she recalls. “It was so sad.”

Abas and her colleagues are exhausted, but they know the third wave of infections is still rising. Claire Wilkinson, another ICU nurse treating a patient in the next room over, says she's noticing the increase in severely ill patients.

“The third wave is just getting started,” she says. “I think that'll be a big challenge this time around.”

Minutes later, across the hall, intensivist Dr. Ali Ghafouri starts rallying team members for an immediate intubation procedure. A 60-year-old patient who had arrived at the emergency room earlier in the morning with shortness of breath is struggling to breathe.

A team of medical staff rapidly donning personal protective equipment from head to toe storms the room with equipment and medication, working fast to treat and reassure the frightened man as he gasps for air.

It's a situation staff at this hospital's ICU say they see every day. The procedure is traumatizing for patients and can leave them in an induced coma for weeks.

Ghafouri says it's an illustration of life on the front line a year into the pandemic. Today, so far, is a bit calmer than the day before, when Ghafouri says the team had to intubate four patients, one after the other.

“That's what life is like here,” says Ghafouri. “People are burning out, including myself and some of my colleagues. We don't know how much longer it's going to be dragging out.”

It's a struggle doctors and nurses in ICUs across the province are facing.

A year into the pandemic, staff at Humber River say they now have more experience treating the disease, but the relentless pace, personnel shortages and much younger patients are weighing heavily on them.

“The patients that are coming in sick with COVID are definitely more acute,” says Raman Rai, who manages the ICU. “They're sicker and they're younger, which is hard for the team to see that.”

The spike in cases has strained intensive care capacity across Ontario, prompting discussions about the possible need to triage life-saving care.

There are about 50 patients in Humber River's ICU on Tuesday, more than 60 per cent of them with COVID-19, Rai says. Staffing has become a challenge as exhausted nurses seek time off to rest. Transfers from other units have helped alleviate some pressure but Rai says she still worries about staffing, especially the lack of ICU-trained nurses.

Across the province, there were 644 patients with COVID-19-related critical illness in intensive care beds as of Thursday, according to Critical Care Services Ontario.

Hospitals are ramping down all non-essential surgeries this week and are transferring sick people across jurisdictions. The government has promised to create up to 1,000 more ICU beds in response to the growing need.

ICU workers, particularly in hard-hit Toronto, witness the human side of the startling numbers firsthand.

At Humber River, after any serious development involving a patient, Olivia Coughlin slips away to make a phone call. As a unit social worker, she is the point of contact for families of the critically ill patients who can't be at the bedside of their loved ones.

Family visits are allowed, though many relatives can't visit because they are also COVID-19 positive. Coughlin says the emotional support work has been harder than she anticipated.

“It's just really horrible, there's no better way to put it,” she says.

She has an office for making phone calls, but today she dials a family from the ICU lounge, just a few feet from the patient's room.

“I know that they're sitting at home around the phone waiting for that update,” she says. “I like to try and do my best to get in touch with them as soon as I'm able.”

Like her other colleagues, Coughlin says she's been struck by the young age of some of the intensive care patients coming in now.

The case of one previously healthy COVID-19 patient her own age - just 28 - stood out to Coughlin.

“I think that really just goes to show that this virus affects everyone, and I wish everyone understood that,” she says.

Two floors above the ICU, respiratory patient Jose Garcia is feeling much better after being admitted to hospital two weeks ago with COVID-19 that strained his breathing.

He is still taking oxygen after a frightening battle with the illness that at one point he thought would kill him.

“The doctors helped me like crazy,” the 67-year-old Brampton, Ont., resident says from his hospital bed.

Garcia doesn't know where he caught the virus. He's retired and he wears a mask when he goes out. Others in his family were also infected with COVID-19.

He doesn't dwell much on his illness though, repeating his eagerness to go home once he tests negative for the virus. His message to others: take the virus seriously.

“People have to be careful,” Garcia says. “Anybody can get it.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 15, 2021.