The province’s decision to delay implementing mandatory measures to control the spread of COVID-19 in long-term care homes may have contributed to the devastating toll that the virus inflicted on residents and staff during the first wave of the pandemic, according to a long-awaited report from Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk.

The province began providing initial infection prevention and control direction to long-term care homes in February, 2020 but in her report Lysyk said that it was mostly “framed as guidance” at the time and that it was “was ultimately up to home operators to decide what actions to take to protect their elderly, frail and ailing residents.”

She said that by the time Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. David Williams issued an emergency order on April 8 requiring that all staff and essential visitors wear masks there had already been 498 confirmed cases among residents, 347 confirmed cases among staff and 86 resident deaths.

Lysk said that Williams then waited another two weeks to issue another emergency order restricting staff from working in more than one home.

That order came nearly a month after officials in British Columbia took similar action.

“In light of how quickly COVID-19 spread in long-term-care homes, every day that implementing mandatory requirements was delayed made a difference in the effort to control its spread,” Lysyk said in her report.

Some measures to free up hospital capacity had ‘unintended consequences’

A total of 1,937 long-term care residents died during wave one of the pandemic, accounting for nearly half of all fatalities in Ontario.

Lysyk said in her report that the province was aware as early as March, 2020 that 98 per cent of the COVID-19 deaths in Italy had involved elderly people with pre-existing conditions and should have recognized the risk the virus posed to long-term care homes.

But she said that the province “delayed mandating, as opposed to recommending certain measures, did not provide clear directions to homes, and did not inspect to ensure that homes were complying with containment measures.”

She said that some other measures taken early in the pandemic to protect hospital capacity, including the transfer of hundreds of alternate level of care (ALC) patients to nursing homes, may have also had “unintended consequences” by “further contributing to crowding and staffing shortages.”

“Given that homes were, on average, at 98% capacity prior to the pandemic according to the Ministry’s occupancy data, these transfers of patients designated as ALC added pressure to the homes, some of which were already struggling to contain the spread of COVID-19,” Lysyk wrote in the report.

16 recommendations

Lysyk wrote in her 107-page report that neither the Ministry of Long-Term Care or the long-term-care homes themselves were “sufficiently positioned, prepared or equipped to respond to the issues created by the pandemic in an effective and expedient way.

She said that despite longstanding concerns the province “had not yet effectively addressed the systemic weaknesses in the delivery of long-term care in Ontario” and had not even required that homes have an emergency plan in the event of a pandemic.

The report makes a total of 16 recommendations, including revisions to the licensing process for long-term care homes that would require them to renovate their facilities to eliminate three and four-bed rooms “within a realistic, but shorter defined time frame.”

It also makes several recommendations aimed at increasing staffing in long-term care homes and improving compliance with infection prevention and control practices.

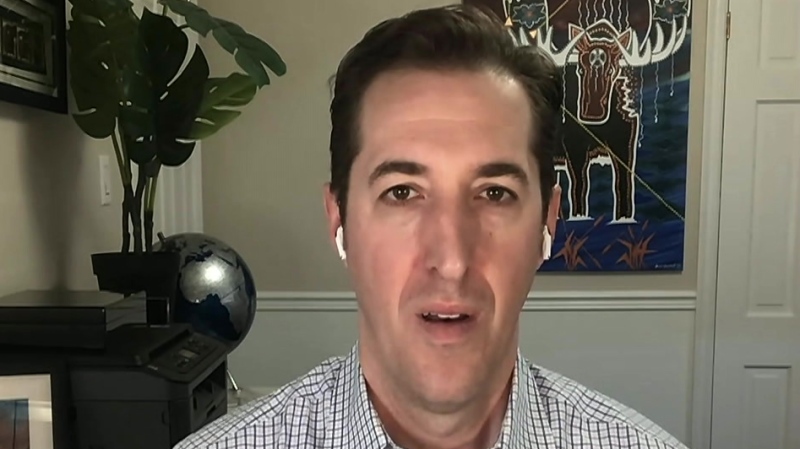

Reacting to the report at Queen’s Park on Wednesday afternoon, Minister of Long-Term Care Merilee Fullerton referred to the sector as a “broken system” largely as a result of inaction by previous governments.

She said that while her government did its best to limit the spread of COVID-19 in long-term care homes in the early days of the pandemic, it was stymied by certain “structural inadequacies” in the system, including a shortage of personal support workers (PSWs).

“It is kind of like running into a burning building. You are trying to save it and you are doing your best but the fire had already started well beyond the pandemic,” she said.

While the report does make reference to several long-standing issues in long-term care, it also suggests that the Ford government missed opportunities to better prepare the sector for a pandemic.

It says that if long-term care homes had been integrated within the broader healthcare sector prior to the arrival of COVID-19, they could have had access to “life-saving expertise on infection prevention and control.”

Instead, many homes were left struggling to interpret “mixed and confused messages coming from local public health units, regarding cohorting, admitting residents into hospitals and the use of personal protective,” the report says.

“When COVID-19 struck what did the Ford government do. They simply chose to neglect the sector. They didn’t even include the long-term care sector in the initial planning around their response,” NDP Leader Andrea Horwath told reporters at Queen’s Park on Wednesday afternoon. “Their plan is five years in the making; they are talking about getting hands on care to residents five years from now in 2025. That is too late. It should have been done already. In fact it should have been done during the pandemic. They should have been hiring those PSWs. Other provinces did it. This government didn’t. They didn’t bother in the first wave and shockingly they didn’t bother during this summer to prepare for the second wave and we all watched as people watched their lives.”