OTTAWA -- The Conservative government plans to amend the law governing the Canadian Security Intelligence Service to give the spy agency greater ability to track terrorists overseas.

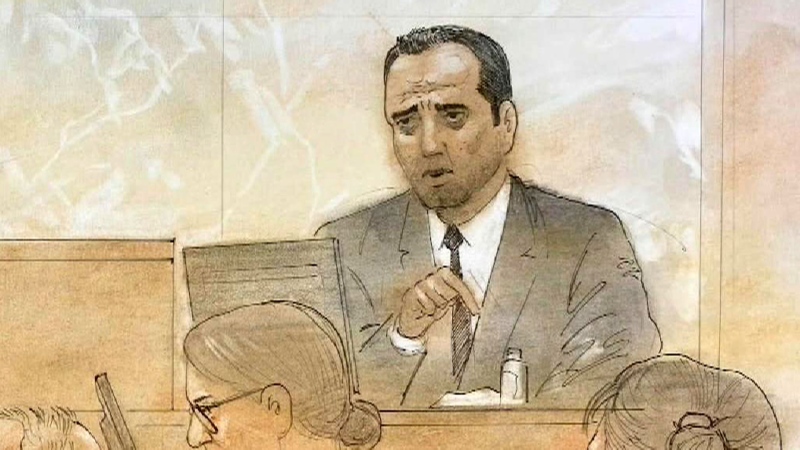

Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney said Thursday the extremist threat has become more complex since the law was passed 30 years ago, adding the dangers to Canada do not stop at the border.

As expected, Blaney said the government would also take steps to ensure CSIS can protect the identity of its sources -- a plan that has already rankled lawyers who have experience defending terror suspects.

The bill, to be tabled next week when Parliament returns, would clarify CSIS's ability to act on threats abroad, he added. "These tools will ultimately allow CSIS to conduct investigations into potential terrorists when they travel abroad, meaning that those individuals will be tracked, investigated, and ultimately prosecuted."

Under the CSIS Act, which took effect in 1984, the spy agency already has the authority to collect intelligence anywhere in the world about security threats to Canada.

Blaney offered no details on how exactly the government would change the CSIS Act, what the revisions would allow the spy service to do that it can't do now, or how sweeping the new source protections would be.

A spokesman for the minister would not answer these questions.

Blaney was joined at a news conference in Banff, Alta., by Andy Ellis, CSIS assistant director of operations, and RCMP deputy commissioner Janice Armstrong.

Ellis said the changes would address a scathing judgment from Federal Court Justice Richard Mosley that took CSIS to task for requesting warrants in 2008 that would allow the spy service to track two Canadians abroad with the technical help of the Communications Security Establishment, Canada's electronic spy agency.

CSIS failed to disclose to Mosley that CSEC's foreign counterparts in the Five Eyes intelligence network could be called upon to help -- something the judge called "a deliberate decision to keep the court in the dark about the scope and extent of the foreign collection efforts."

Canada and other western nations fear that citizens who travel overseas to take part in the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant's guerrilla-style battles could come home with intent to do harm.

The federal plan to bolster security powers follows a recent statement from the RCMP that the national police force has about 63 active investigations on 90 suspected extremists who intend to join fights abroad or who have returned to Canada.

Extending protection for informants could mean defence counsel and even judges would never have the right to question human sources who provide information on behalf of CSIS in court proceedings -- such as when the government attempts to deport a suspected terrorist using a national security certificate.

Ottawa lawyer Norm Boxall, who represents Algerian refugee Mohamed Harkat in a security certificate case, said he is "far from convinced" the spy service needs the new privilege.

"The onus should be on them to establish the need to do this," Boxall said in an interview. "On the public record, there isn't the evidence out there to support this."

Toronto lawyer Paul Copeland, who previously represented Harkat, said giving the class privilege to intelligence informants would be "highly dangerous."

"The only way you test evidence, in my view, is by cross-examining on it," he said. "I think if they pass this class privilege, nobody will ever get at a human source in a national security case."

Copeland later served as a special advocate -- a security-cleared lawyer who reviews and tests the federal evidence -- in Harkat's certificate case. He remains on the roster of special advocates periodically called to take part in security proceedings.

The Federal Court of Appeal said in 2012 that human sources recruited by CSIS did not have the sort of blanket protection that shields the identities of police informants, even from a judge.

In the case of CSIS, this is instead decided on a case-by-case basis.

The Supreme Court agreed in a May ruling on the national security certificate regime that there should be no overarching privilege for CSIS sources. The high court said the security certificate generally ensures that their identities remain "within the confines of the closed circle" formed by the reviewing judge, the special advocates and federal lawyers.

The court noted the judge reviewing a certificate has discretion to allow the special advocates to interview and cross-examine such informants in a closed hearing, but said this should be "a last resort."

Making it standard practice to cross-examine CSIS sources, even behind closed doors, could "have a chilling effect on potential sources" and hinder the spy service's ability to recruit new ones, the court added.

Two judges -- Rosalie Abella and Thomas Cromwell -- dissented on the issue, saying CSIS informants are entitled to an assurance that the promise of confidentiality will be protected. "This can only be guaranteed by a class privilege, as is done in criminal law cases."

Copeland points to a notorious chapter of the Harkat case in arguing there is good reason to test the credibility of human intelligence sources.

In a 2009 ruling in Harkat's case, Justice Simon Noel said CSIS "undermined the integrity" of the Federal Court's work by failing to disclose relevant details of a polygraph examination of a source. CSIS neglected to tell him a secret informant failed portions of the lie-detector test -- a lapse the spy service itself has called "inexcusable."

Currently police can use information from secret informants to obtain search warrants or wiretap authorizations without fear the sources will be subject to cross-examination. However, if those same informants are used as evidence of an accused person's guilt, the protection does not apply.

The new federal bill should include the same sort of protection to ensure fairness for someone facing allegations in a security proceeding, Boxall said.

CSIS makes "every attempt to ensure that the information we're getting is accurate and corroborated," Ellis said. "So we do not act on single-source information."