A new study out of Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) has found the upcoming service cuts to Toronto’s transit system will disproportionately impact the city’s marginalized communities.

The report, released by TMU’s Dr. Raktim Mitri and Dr. Tess Peterman Thursday, examines the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) service changes going into effect on March 26. A total of 39 routes will be impacted – one streetcar route, two subway routes, and 36 bus routes – making up 20 per cent of all service.

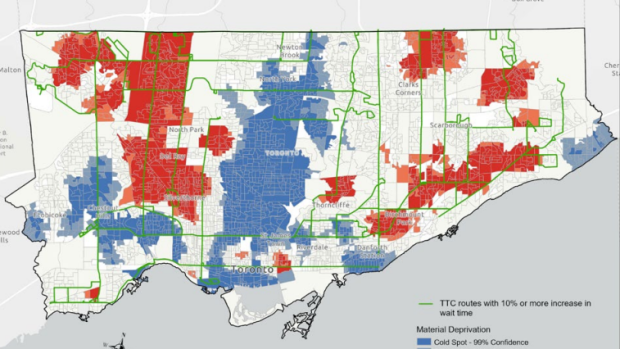

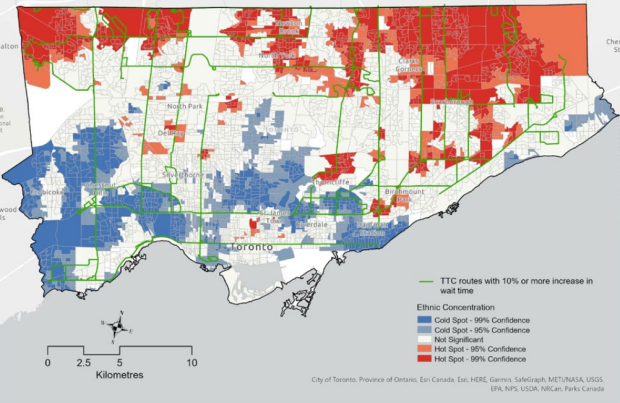

The researchers found a correlation between the location of the most-affected TTC routes and lower-income areas in which residents rely more heavily on public transport – according to Mitri and Peterman, more than 80 per cent of the routes set to be most impacted by the cuts move through neighbourhoods with higher poverty rates, numbers of immigrants, and unemployment rates.

The service reductions will come into effect just days before the commission is set to increase its fares for youth and adults by 10 cents.

“Everyone uses public transit in a big metropolitan like Toronto, but then some people need it more than others, whereas, for others, it’s more of a choice,” Mitri told CTV News Toronto Thursday.

“So when we are planning for public transportation, it is important that the areas where there's higher concentration of poverty or lower income people or immigrants, that those areas are better serviced by public transportation.”

When reached for comment, the TTC thanked the researchers for their feedback and observations.

“We also appreciate that they recognize our work to apply an equity lens to our service planning decisions, and the financial challenges we face as we contend with a 25-30 per cent loss in ridership this year,” spokesperson Stuart Green said in a written statement to CTV News Toronto.

Green said, when it comes to future service changes, 80 per cent of service will remain unchanged, and that the impacted routes will only see marginal changes.

The commission says the upcoming changes will protect service on its busiest routes and that a majority of the service reductions and longer waits will take place during off-peak times. But, advocates claim the move only services to increase barriers to marginalized communities, while making it more difficult for the TTC to recover from low ridership levels caused by the pandemic.

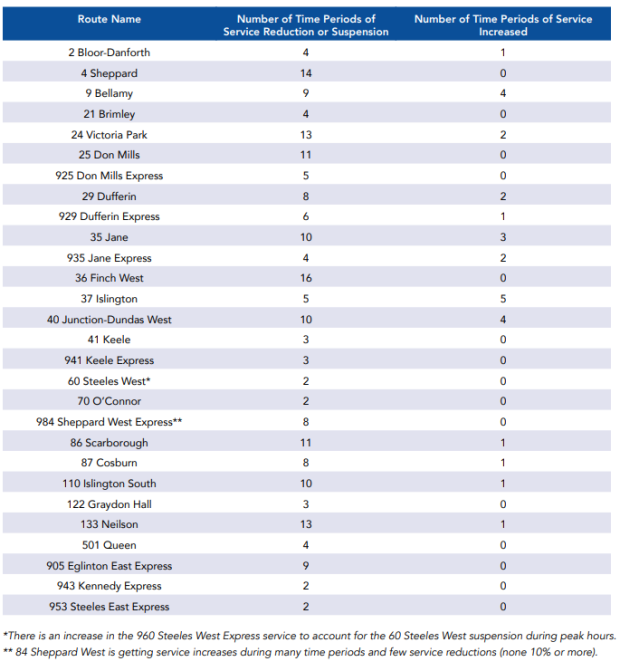

WHICH ROUTES WILL BE AFFECTED?

The report focused on the routes with the most affected service – ones with a 10 per cent or more reduction or a complete route suspension that would lead to longer wait times. This equates to 28 of the 39 routes that will see service changes.

The researchers found that, while some of the reduced service is in high-transit areas, the majority are in neighbourhoods that are not transit hot spots and where “overall transit ridership was not high, pre-pandemic.”

These areas, the researchers found, are often the same in which marginalized communities work and live.

Specifically, they found 93 per cent of the routes that will experience at least a 10 per cent increase in wait times go through or connect to a neighbourhood with higher poverty rates.

These neighbourhoods, mostly in east and west ends of the city, are often home to transit users that rely on the system for employment, city-wide services, and other needs.

The researchers said they observed a similar pattern when they compared the impacted TTC routes with local dependency, or unemployment rates.

Twenty-two of the 28, or 79 per cent, TTC routes that will experience at least a 10 per cent increase in wait times travel through or connect to a neighbourhood with higher populations of unemployed individuals.

Lastly, 24 of the 28 most-impacted routes, or 86 per cent, go through neighbourhoods with high concentrations of recent immigrants and “visible minorities.”

Many of these neighbourhoods are located toward the north of Toronto, including in Scarborough, North York, and Etobicoke, the report found – areas that already had poor public transport accessibility.

“As a result, it would affect residents’ well being, but more broadly, it adds another barrier for them to participate in employment, social activities, entertainment – everything just becomes more difficult because these locations would now become less accessible,” Mitri said.

CALLS TO DROP THE CUTS

The service reductions were first proposed alongside the TTC’s 2023 operating budget on Jan. 4, although the specifics were not made publicly available until late February.

The TTC underlines that this budget will deliver service based on post-pandemic ridership levels, while also investing $2 million for service in 13 Neighbourhood Improvement Areas, such as Stanley Greene neighbourhood in Downsview, and Jane and Finch in Toronto’s northwest end.

Since 2020, the TTC has been operating at reduced service levels amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, the TTC is offering about 96 per cent of pre-pandemic service levels and seeing about 68 per cent of pre-pandemic ridership.

When the new service changes take effect, the TTC says service levels will drop to 91 per cent of pre-pandemic service.

The team at TMU called the move “unjustified at a time when all levels of the government are committing to address affordability and inequality.”

Advocacy group TTCriders has also been vocal in condemning the cuts. Following the 2023 budget proposal, the group released a statement saying the service cuts “will leave transit users waiting longer for their bus, streetcar, and subway.”

“Service cuts and fare increases will only drive more transit users away, reducing safety and wrecking Toronto’s chances at meeting our climate goals,” the group wrote.

TTC SAYS CHANGES WILL BE MARIGINAL

Amidst the calls to sustain current service levels, the TTC is maintaining that changes will be minimal on affected routes.

“Thirty-six per cent of schedule changes will result in no change or a shorter wait time,” Green said. “[And] just over half of all schedule changes will result in a longer wait time of between 30 seconds and three minutes.”

Green pointed out that, while the report characterizes the service changes in percentages, most will mean an increased wait of approximately 30 to 120 seconds.

“For example, a transit user accustomed to waiting four minutes and thirty seconds for their bus, may soon wait five minutes between vehicles,” he said.

Two-thirds of the routes that will change come Sunday will also have a service reliability improvement plan issued for them, which Green says will make service more predictable following reductions.

SOLUTIONS

To improve service and alleviate financial pressure on the TTC, TMU researchers are calling on the provincial government to provide more funding to the system.

“We recognize the difficult financial challenges that the TTC is currently facing,” they wrote. “But our hope is that these service cuts will be short-lived while the TTC, the City of Toronto, and the Province of Ontario explore other sources of revenue to fund the operation and future growth of Toronto’s dated public transit infrastructure.”

On Feb. 8, more than 100 researchers in the Toronto area wrote an open letter to the TTC, saying the proposed service cuts would lead to more congestion, a weaker economy, and poor environmental and health outcomes. Their letter also called for the implementation of alternative revenue sources across all three levels of government.

“How policymakers respond to the lingering effect of the pandemic is what will actually determine whether the pandemic was a brief shock to our transit system or the beginning of its demise,” they wrote. “We strongly urge governments to adopt progressive policies that can shore up transit service in the nation’s largest city until ridership recovers.”

When asked for actionable solutions, Mitri said the provincial government could earmark a larger proportion of the gas tax revenue for the transit system, while the municipal government could increase parking levies and rates as a means of increasing revenue, among other options.

"Cities are the creatures of the province [and] the province has to give cities the power to generate the revenues, which is very important," Mitri said. "Unfortunately, historically, the province of Ontario has been very reluctant to support or fund public transportation operating budgets, which has created the problem that we have today.

"We feel this need to change," he said.