A First Nation in northern Ontario has expanded its search for the source of a lung infection that has killed two people and sickened at least 12 others, the First Nation's chief said Wednesday.

Constance Lake First Nation, a community of over 900 residents, declared a state of emergency on Nov. 22 after probable cases of blastomycosis and three deaths came to light.

Blastomycosis is typically caused by a fungus that grows in moist soil, leaves and rotting wood. It is spread when a person breathes in small particles of the fungus into their lungs, but does not spread from person to person or animals to people.

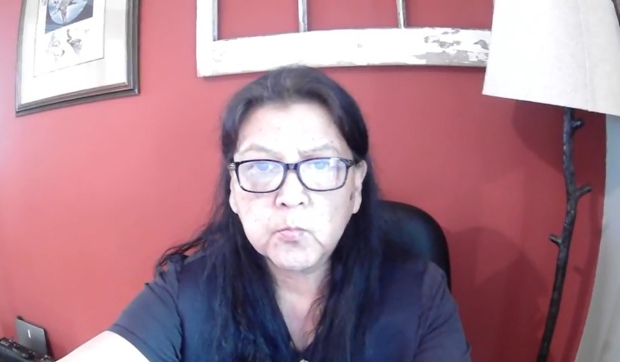

Constance Lake First Nation Chief Ramona Sutherland said 29 samples have been taken from various locations in the community so far, but they have all come back as negative for blastomycosis.

Sutherland said the “whole reserve” is now being searched for the source of the lung infection.

“We're looking for the source and hopefully we'll locate that,” she said in a phone interview.

Indigenous Services Canada said the negative environmental results are “not abnormal due to the difficulty in isolating blastomyces spores from environmental samples,” adding that additional test results are “forthcoming.”

The federal department noted the cases of blastomycosis in Constance Lake First Nation “have not been linked to residential homes” and that it has consulted a blastomycosis specialist to “review the current approach.”

As of Wednesday, Sutherland said there are 12 people who are confirmed to have the lung infection and nine people in hospital with probable cases.

Another 119 people are under investigation for the infection, which Sutherland clarified means that they went to the hospital with symptoms of blastomycosis, such as a cough, fever, chills, fatigue and/or difficulty breathing.

Sutherland said autopsies were done on two people who recently died in the community and “both confirmed blastomycosis.”

She encouraged community members to get checked out if they are experiencing any symptoms and said those with cases under investigation should get checked out every two days until they're cleared of symptoms.

Indigenous Services Canada said it's working directly with Sutherland, the Matawa Tribal Council, the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority, the Porcupine Public Health Unit, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, as well as other health partners to “identify and address community needs and ensure those affected have access to the resources they need.”

“Indigenous Services Canada extends its deepest condolences to the community and the families impacted by this cluster of respiratory illness,” the department said in a written statement.

ISC said it's providing surge nursing support, funding transportation for hospital visits and has assigned environmental public health officers to help conduct interviews with affected individuals to assess any “common links between cases,” among other measures.

Sutherland said there are also traditional healers and counsellors for adults and youth in the community amid the outbreak.

Meanwhile, the hospital in Hearst, Ont., has closed its operating room and is setting up an observation unit for probable cases and persons under investigation for blastomycosis from Constance Lake First Nation, with a stock of anti-fungals on hand, and the provincial government is providing “surge acute care support” for the hospital, ISC said.

The province is also “expediting relevant testing to ensure results are available as soon as possible,” ISC added.

Sutherland said investigators believe the fungus suspected of causing the infection in Constance Lake First Nation is currently dormant due to snowy conditions.

The federal department echoed these remarks, saying that “blastomyces, the organism that causes blastomycosis, does not thrive in winter weather” and that exposure is “more common in the summer and fall.”

“That said, the number of cases is very concerning and the department is mobilizing all efforts to support the community,” ISC said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 8, 2021.