Disclaimer: Some details of this story are graphic in nature. In line with medical and court records obtained by CTV News Toronto, Amos is initially referred to by their legal name, Vanessa, in our text. We acknowledge that in the last months of their life, they went by the name Ezra, using they/them pronouns.

Just after 8 p.m. on March 31, bystanders at Bathurst and Bloor streets in Toronto’s Mirvish Village reported hearing a crash, followed by glass raining down from a construction site above.

Then, a body hit the sidewalk.

The morning before Vanessa Amos, who in the months prior went by the name Ezra, fell to their death, at least three medical professionals at Toronto Western Hospital noted Amos expressed an intention to die.

Amos, a 22-year-old queer person living between Toronto and Hamilton, Ont., was involuntarily admitted to hospital on March 30 after a police interaction at Bathurst subway station landed them under arrest.

“Nessa did exactly what they said they were going to do,” Brandy Schlemko, Amos’ mother, told CTV News Toronto in an interview. “And they let my baby walk right out of there.”

While in hospital, medical records obtained by CTV News Toronto indicate Amos expressed the intent to end their life to hospital staff at least three times throughout their stay — at one point, detailing how they might carry out the action — yet was discharged after 12 out of the maximum 72 hours the Ontario Mental Health Act (OMHA) allows.

When a patient is admitted to hospital under the OMHA, they can initially be involuntarily held for up to 72 hours, after which a physician must assess whether they would benefit from an extended admission, or whether the patient can be safely discharged.

While the hospital maintains it followed triage protocols and prioritized patient autonomy, experts say Amos’ 12-hour stay is indicative of a larger problem – a provincial healthcare system pushed to the brink, rendered at times incapable of providing meaningful treatment to patients in mental health crisis.

'A BRILLIANT LIGHT'

The five months prior to Amos’ death had been coloured with tragedy and trouble. Those close to them said they seemed to be displaying symptoms of psychosis, and that frequent police interactions and a lack of secure housing left them distressed and destabilized. During the night they spent in hospital, they told doctors they had recently suffered a miscarriage.

To Jesse, a Toronto-area resident to whom CTV News Toronto is granting anonymity, Amos was chosen family.

“Much of their later struggles were aggravated by external stressors – they were targeted for being genderqueer, for being Black, for being tenacious,” Jesse said.

In November 2021, court documents show that Amos was arrested and charged with assaulting a police officer while protesting encampment clearings alongside Hamilton Encampment Support Network (HESN).

Three months later, the Hamilton home they were renting with a friend burned down. Hamilton Fire cited a space heater as the cause.

On a GoFundMe created by Amos to help recoup the costs of the previous months, Amos wrote they felt they had gone “from the pot to the frying pan” when describing the loss of their home.

Seven days later, Amos was again arrested – this time, at the site of their burned home.

In a separate update posted to GoFundMe, they wrote they had gone to the home to salvage personal effects. Police arrived and Amos was charged with one count of mischief under $5,000 for breaking a window, and two counts of assaulting an officer. Amos alleged that police brutalized them during this interaction.

In a photo Amos shared shortly after, their right eye appears tro be swollen and shadowed by a purple bruise.

In March, the Crown dropped the assault charges placed on Amos on the condition that they not cross police tape, interfere with police operations relating to the homeless, or participate in or organize any unlawful demonstrations.

“In the last week of their life, they faced violence by every system [..] at a time they needed support most acutely,” Jesse said.

“But Ezra should be remembered as more than someone failed by systems: they were a brilliant light fighting for their shine with the many social forces that tried to dampen it.”

To loved ones, Amos was more than the sum of the events that led up to their final days.

“They were a lover of all art forms, including tagging and painting, particularly creating collective and communal paintings,” Jesse recounted. “Ezra taught me how to chop wood, build a fire, string up a tarp shelter in the pouring rain.”

“To say that they did not struggle with mental health is an untruth - they struggled most of their life, but this did not define their life,” Jesse said.

Schlemko speaks of a young person who took to new skills quickly, and fostered a love for animals.

“The last photo I ever took of Nessa was with my horse, Jake” she said.

By spring 2022, their mental health had worsened to the point of crisis.

On March 30, the day before they were admitted to hospital, Amos was allegedly caught on TTC security footage walking on the subway tracks at Bathurst Station. After what officers called “an exchange of blows” with a responding special constable, Toronto police were called to the scene. They said Amos was attemping to take their own life while on the tracks.

The interaction, in which Amos is alleged to have further assaulted responding officers, landed them under arrest, charged with assault for the fourth time in as many months, and transported to hospital where they were detained under the Ontario Mental Health Act.

ADMITTED UNDER THE OMHA

Amos was admitted to Toronto Western’s emergency department at approximately 11:30 p.m., before being sedated, restrained for two hours, and admitted into the psychiatric unit, according to their medical records.

During an assessment the night of their admission, staff deemed Amos to be at a chemically elevated risk of harming themselves or others.

The morning of their discharge, Amos was assessed for a second time by a psychiatrist. The physician noted Amos “sobbed occasionally” throughout the interview and, at multiple times, requested medical assistance in dying. Amos is said to have threatened to “try to find a knife” or “jump off a building.” When probed further, and asked which building, they responded, “a tall one,” notes state.

At this time, Amos also told staff they had suffered a miscarriage just days prior.

Staff noted Amos said they’d been feeling “low” for months, but refused antidepressants or counseling.

At approximately 11:30 a.m., nearing the end of the interview, documents state Amos asked to be discharged, citing a court date for later that day that they “urgently” needed to attend.

Both Hamilton Court Services and Toronto Police Service confirmed to CTV News Toronto there was no court date issued for Amos for March 31. They were not expected again in court until May 26.

At approximately 12:20 p.m., they were given a TTC token, had their belongings returned to them and discharged.

Just over eight hours later, they were dead.

When reached for comment, the University Health Network, which oversees Toronto Western Hospital, told CTV News Toronto it “does not discuss individual cases, given [its] responsibility to maintain the privacy of individuals on all matters of their health information.”

“Any patient presenting at our Emergency Department is triaged, symptoms are evaluated and a plan of care is discussed with the patient,” Gillian Howard, spokesperson for the hospital, told CTV News Toronto

“Decisions to hold someone in mental health crisis are re-evaluated throughout the period of the ‘hold,’” Howard said, adding that “the rights of an adult patient to have autonomy over the decisions regarding their care are paramount.”

“When a ‘hold’ is removed it is a clinical decision, in concert with a discussion with the patient, and those discussions include what follow-up care should take place,” she said.

‘A REAL PLAN’

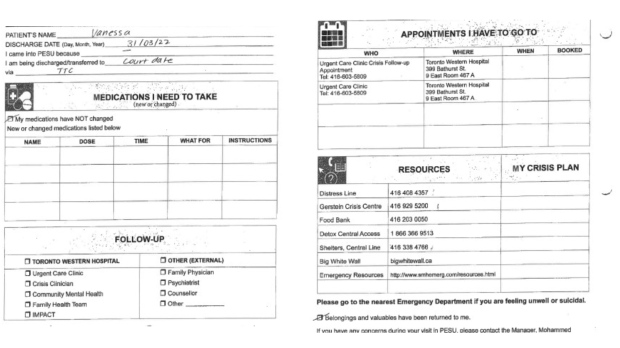

Nowhere in the discharge documents does it indicate Amos was scheduled for a follow-up appointment. Sections titled 'My Crisis Plan' and 'Follow-Up' were left blank.

Instead, a number of crisis hotlines are listed. None of the resources referenced pregnancy loss or the LGBTQ2S+ community. Clinical notes suggest Amos was told to return to the emergency department if they found themselves in crisis again.

Patient advocate and Executive Director of the Empowerment Council at the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health in Toronto, Jennifer Chambers, told CTV News Toronto that, if possible, “a warm handover” is always preferable when discharging a patient.

“A warm handover is when a staff member or service provider contacts another one prior to discharge, and so a patient's being referred or set up with an appointment before they go, but it's also not something emergency departments generally have the resources to deliver,” Chambers said.

Sean Hayward, medical litigator from Dundas, Ont., says that comprehensive discharge plans for mental health patients are vital, but often, the care and attention required to be put into those plans require a significant amount of time and resources.

“When you’re evaluating a patient and whether they’re going to be safe upon discharge, you have to have a real plan,” Hayward said. “It needs to be discerned that the patient has things that are motivating him or her to stay alive.”

Comprehensive plans can include a number of things, such as confirming if a patient is receiving therapeutic services elsewhere, according to Hayward.

Amos’ records show that at least two medical professionals ascertained Amos had existing therapeutic relationships – with both a cognitive behavioural therapist, and the Youth Wellness Counseling services in Hamilton. Nowhere in the documents is it noted that staff contacted either.

A comprehensive discharge plan could also include “confirming where a patient might stay upon discharge, or contacting individuals identified to be in the patient’s community,” Hayward said.

In the 12 hours that Amos was admitted to hospital, treatment didn’t reach that point. As far as their mother is aware and medical records indicate, staff made no efforts to contact anyone in Amos’ community before discharging them.

“They could have saved their life with one phone call – to me, to a friend, to somebody,” she said. “Shouldn’t somebody have been called?”

ONTARIO’S EMERGENCY DEPARTMENTS

Recent Ontario Health data paints a picture of emergency rooms pushed past the brink of capacity.

In September, there was an average of about 946 patients waiting for a hospital bed in an emergency room at 8 a.m. daily across the province. This represents a 44.7 per cent increase compared to September 2021.

According to data by Health Quality Ontario (HQO), those patients spent an average of 21.3 hours in ERs waiting to be admitted.

“I think we’d all agree Ontario emergency departments are wholly overtaxed in a variety of ways,” Chambers said. “So it's an ever-increasing demand on emergency departments without the means to really meet that demand which means that very, very difficult calls are constantly having to be made about who to keep and who to let go.”

Ontario’s Ministry of Health did not provide comment when asked if Ontario emergency departments currently have adequate staffing levels and resources to meaningfully assess patients admitted under the Mental Health Act, but underlined that UHN has “adequate” staffing at this time.

‘AVOID THE PAIN’

Ultimately, Hayward says the inability to devote needed resources to mental health can lead to severe and tragic outcomes.

“These patients require a lot of resources to keep them safe, whether it be for monitoring, having facilities to avoid inpatient deaths, or just in terms of time with a psychiatrist,” he said.

“An inability to devote the necessary resources or failure to think critically about a patient or discharge too early, [can] result in deaths or very, very serious injury.”

But for Schlemko, talks of policy and health-care reform won't bring her child back.

“The bottom line is Nessa’s gone,” she said. “There’s nothing I can say or do.”

“Nothing is going to change what happened, but knowing that people are listening is what gives me a little tiny piece of mind because Nessa’s voice is gone,” she said.