Results of an anonymous survey to be released in the fall by National Defence will shed more light on the extent of military sexual assault, including what has been called the silent crime of male-on-male rape.

Almost 68,000 troops, 86 per cent of them men, were asked last August to voluntarily complete the Canadian Forces Workplace Harassment Survey. It asks respondents their gender, years of service and rank, along with 100 questions ranging from personal harassment to whether they've ever been raped.

It's the first time the military has done such a survey since 1998.

Results could provide valuable insight into the extent of military sexual violence -- an issue that former soldiers and frontline social workers say is rarely reported.

The extent to which men in the military are sexually attacked by other men is even more cloaked in silence, they say.

That's changing in the U.S. with congressional efforts to address the issue, and the premiere Saturday of a new documentary called "Justice Denied." It features survivors of what is described as male military sexual trauma.

According to a 2012 anonymous survey released last month by the U.S. Department of National Defense, an estimated 6.1 per cent of active duty women and 1.2 per cent of men were victims of unwanted sexual contact. That translates to roughly 12,000 women who were assaulted and 14,000 men -- up from an estimated 19,300 victims in 2010.

A fraction of those incidents is formally reported.

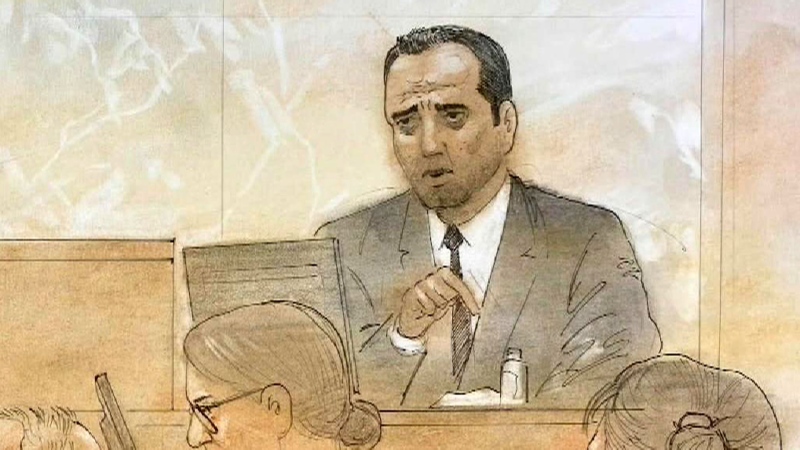

"Victims can be male or female, just as the perpetrators are quite capable of being male or female," said Brian Lewis, who earlier this year became the first man to testify before U.S. Congress about male rape in the military.

He was a 20-year-old U.S. Navy petty officer third class in 2000 serving on USS Frank Cable in Guam. He said a superior took him off the ship for dinner one night.

"He began making sexual advances, which I had pushed off. And then at that point he pulled a weapon (a knife) and had me perform some sexual acts.

"After that point, he penetrated me," he said. "A friend found me bloodied in the barracks."

He says his superiors told him not to make a formal complaint, something he says happens all too often. It's why he and others are pushing for U.S. legislation that would take the reporting, investigation and prosecution of sexual assault outside the chain of command to an independent office with military and civilian oversight.

"I could be labelled as a homosexual and discharged," he said he was told at the time. "The other reason was that it would make the command look bad."

Phillip Millar, a lawyer representing several women who allege they were sexually assaulted by a now retired Canadian Forces medical technician, says the military's "macho culture" keeps men quiet.

"It's hard to even know what's happening because the culture discourages reporting so much," he said.

Millar, a former infantry officer who retired from the Canadian Forces in 2005 after 12 years of service, said he didn't hear of members being told not to report sexual violence. But he described an unspoken sense that the victim will be blamed and marked as weak.

Alain Gauthier, acting director general of operations for the Canadian Forces ombudsman, made the same point last December at a hearing for the Commons standing committee on the status of women.

"There's a clear fear of reprisal if people move forward and make an official complaint, either on harassment or anything else," he said when asked about sexual harassment.

Lewis, 33, tells his story in "Justice Denied," and has gathered related research as a graduate student who plans to become a lawyer to help other veterans.

He said it's crucial that Canadian officials get a better handle on the extent of military sex crimes by conducting anonymous surveys and offering services for male victims.

"In the Canadian Forces, I think that male sexual violence is occurring very frequently."

Eighty-five per cent of U.S. military members are male and the majority of sexual assault victims as estimated by the Department of Defense -- about 55 per cent -- are men, Lewis said.

Roughly the same demographic applies to the Canadian Forces, but it's unclear the extent to which male sexual assaults are happening.

There were 176 sexual assaults reported to Canadian military police in 2010, the most recent statistics available. That compares to 166 incidents in each of the two years before and 176 reported in 2007. Gender is not specified.

Military members made 290 harassment complaints between 2006 and 2013 resulting in 87 investigations, public affairs officer Michele Tremblay said in an email.

Frontline social workers say the issue is vastly under-reported as it is in the civilian population. They say survivors fear being revictimized by skeptical investigators and a court system that often throws out cases for lack of evidence.

"Within organizations that are primarily male that are sub-cultures, that have a hierarchical framework, sexual violence is there," said Angela Marie MacDougall, executive director of Battered Women's Support Services in Vancouver.

"It's there and it's not discussed because of ... all the stuff around homophobia and all the stigma around being a victim."

Michael Matthews, who says he is a U.S. military rape survivor and appears in "Justice Denied," said he has met many other men, including Canadians, who've endured similar ordeals. He said most such attacks are about power and are committed by heterosexual men.

"A lot of people think it's a gay issue and it's not," he said in an interview.

Matthews says he was a 19-year-old airman first class when he was knocked unconscious, raped and beaten by three servicemen on the Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri in 1974.

He served 20 years in the military, attempted suicide six times and never spoke of what happened for 30 years, he said.

His wife Geri Lynn Weinstein-Matthews, a social worker who co-directed "Justice Denied," said public awareness is vital.

"I would like people to realize this is a systemic issue and it's not going to go away," she said. "We have embedded felons -- serial rapists -- that are walking around free and dangerous.

"This is an issue that costs dollars and cents and lives. And it's something that has to be looked at immediately."