Toronto’s most vulnerable residents along with those who support and advocate for them say they had no choice but to band together during the pandemic to ensure people experiencing homelessness and those at risk of becoming unhoused were taken care of and they’re now sharing some of those stories.

"Dredz,” who has stayed at a number of encampments in downtown Toronto parks, said over the last two and a half years he and many others experiencing homelessness have been repeatedly let down by the system meant to take care of and protect them.

He said unhoused people in Toronto supported each another during the pandemic by setting up tented communities in local green spaces, making sure their friends were fed and had access to health care and other supports, and offering comfort during the hardest times. Many times these efforts to build community were met with police violence and intimidation, he noted.

And while losses and hardships happened frequently, in the end, Dredz said they somehow got by, especially those who were able to ask the right questions so they could get the assistance they needed.

Frontline workers also worked tirelessly to keep people during the pandemic alive while contending with reduced and closed programs and services often due to deep budget cuts.

Over the last two and a half years, at least two Toronto advocacy groups also took the city to court to fight for safer shelters with minimum physical distancing requirements and the right to camp in city parks in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Diana Chan McNally worked for the Toronto Drop-In Network during most of the pandemic and said the life-saving services she helped coordinate and advocate for were often a last priority.

“We were the only spaces that stayed open the entire time. We never shut down at all,” she said, adding despite seeing a “steep, steep increase in need,” several community-based services and local agencies saw their city funding significantly slashed in 2022.

McNally, who is the author of Encampments to Homes: A Path Forward, which provided a series of policy recommendations to the City of Toronto, also fought hard during the pandemic for access to vaccines as well as personal protective equipment for both workers, volunteers, and community members.

During the pandemic, the city, among other things, organized the emergency distribution of 310,000 additional N95 masks for shelter clients and set up a pilot COVID-19 vaccine program in the shelter system.

Further, with an additional funding from the province, Toronto expanded its shelter system by opening more than two dozen temporary shelter-hotel sites as well as increased others supports for people experiencing homelessness like utility and rent banks to help keep low-income individuals in their homes.

Moving forward, the city’s goal through its HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan is to approve 40,000 new affordable rental homes, including 18,000 supportive dwellings and 1,000 modular residences.

For long-time harm reduction worker and advocate Zoe Dodd, the pandemic has been marked by the loss of many people she’d come to know and love to the drug poisoning crisis, which she says was often exacerbated by trauma, grief, and stigma.

Dodd said many of those she lost over the last two-and-a-half years had stayed in the city’s shelters, most of which don’t have supervised places for people who use drugs to consume unregulated substances.

According to City of Toronto data, there were at least 78 suspected drug overdose deaths in 2021 in the shelter system. So far this year, preliminary data up to the end of June indicates an estimated 22 people died of a drug overdose while at a city-run shelter.

Sandra Campbell, of Toronto Urban Native Ministry, saw first-hand how many of the city’s Indigenous peoples were disproportionately impacted during the pandemic, while Jennifer Jewell, who gets around with the assistance of an electric wheelchair, lived in a downtown shelter-hotel for the last 23 months an said the experience “severely compromised” her human rights as a disabled person. Jewell moved into permanent housing just three weeks ago.

“The system destroyed me as a disabled client,” she said.

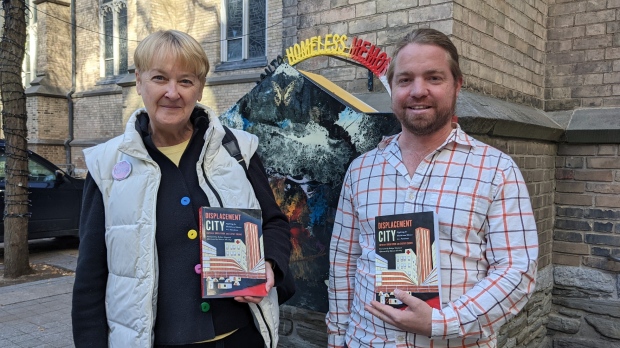

For more than a year, street nurse Cathy Crowe and outreach worker Greg Cook compiled dozens of heart wrenching stories of survival into a 280-page book titled Displacement City: Fighting for Health and Homes in a Pandemic.

The book, which is dedicated to “each person who died without housing in Toronto during the COVID-19 pandemic,” was launched on Nov. 9 at the Church of the Holy Trinity. It features pieces by more than 30 contributors, including Dredz, McNally, Dodd, Campbell, and Jewell.

“The city has its own narrative of what went on, but we felt it was important to share the voices of people really affected and those working to support them” Cook told CP24 Wednesday afternoon, adding he hopes Displacement City will encourage the city to “pause and listen to people” before acting.

“The official story isn’t actually what happened on the ground. … We wanted a record of the last two and a half years that is the truth for people to see, not the official sanitized narrative.”

Crowe, who called Displacement City a “testimony” to what Toronto’s unhoused population experienced during the pandemic, said their goal was to “give voice to the people who fought for the city’s most vulnerable during the pandemic.”

“Hopefully this is a book that can show people what can be done,” Crowe added, noting she wants to see a post-pandemic inquest undertaken to examine the inequities marginalized people faced and make recommendations to ensure they don’t happen again.