Uber's vice-president and global head of public policy wants Ontario to speed up its efforts to deliver gig economy legislation and act on its pitch to boost gig worker benefits.

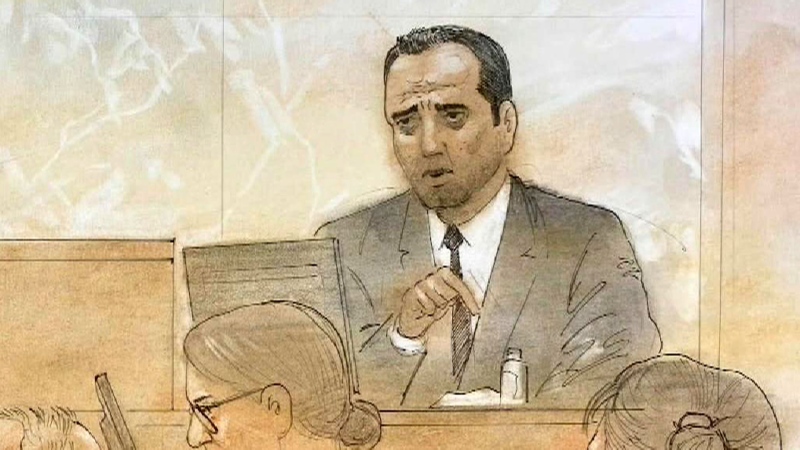

“We would like to go further and faster and more quickly than perhaps the government is ready to do,” said Andrew Byrne, in an interview with The Canadian Press during a visit to Toronto this week.

His comments come a year after Ontario's Working for Workers Act, known as Bill 88, received royal assent, but implementation of the legislation, which delivers minimum labour standards to gig workers, has been slow.

The bill requires digital platforms like Uber to offer minimum wage, provide information on how pay will be calculated, give workers being removed from the platform two weeks' notice and ensure there are mechanisms to resolve disputes that leave workers free from reprisals.

Byrne wants more.

“It's great to give drivers more transparency and I think a minimum earnings guarantee in Ontario is a really great first step, but to really deliver exactly what we think the future of the industry looks like, I do think you need portable benefits,” he said.

Portable benefits are a cornerstone of the Flexible Work+ model Uber has been pushing in Canada in recent years. The model asks provinces and territories to force app-based companies to create a self-directed benefit fund to disperse to workers for prescriptions, dental and vision care, RRSPs or tuition.

Some workers' groups, such as Gig Workers United, dislike the pitch because they see it as Uber's way of avoiding classifying workers as employees, who would be entitled to minimum wage, vacation pay and parental and medical leave.

Uber drivers and couriers are considered to be independent contractors because they can choose when, where and how often they work, but in exchange, they have no job security, vacation pay or other benefits.

Uber maintains its research shows the bulk of drivers and couriers want more benefits but not to be classified as employees because that could take away their flexibility to work when and how often as they'd like.

Asked about Byrne's call for the government to move faster and further, provincial Labour Minister Monte McNaughton pointed out Ontario is the first to provide core rights to gig workers, including health and dental care.

“These foundational rights have no precedent or template in Canada to pull from. By providing drivers and couriers with these protections, we're raising the floor, not setting the ceiling,” the minister of labour, immigration, training and skills development wrote in a statement.

“Nothing is preventing large corporations from providing their workers with higher pay, vacation time, or other protections, tomorrow, if they chose to do it.”

By Byrne's count, there are over 600,000 people earning money through Uber in Canada, including some using the platform for as few as two hours a week and others closer to full-time work.

Data that Uber tabulated in December showed many joined the platform in the last six months, when the company detected a “significant” increase in sign-ups. The last three months has amounted to its busiest sign-up period ever with 65 per cent of the new workers saying they joined to help with high inflation, unexpected expenses and to mitigate reduced hours or jobs losses.

About 75 per cent of them are working fewer than 15 hours per week for Uber and the same amount said flexibility was a key reason for signing up.

“They could be working part time for someone else in the gig economy. They could also have a full-time job, but we don't necessarily know that and so that's why we feel so strongly that we need to build on the Ontario government's reform proposals and build in a portable benefits system,” Byrne said.

“These people who are working little hours in different places should be able to get the benefit of all of their hours across all the different things and the platforms that they're working on.”

To bolster that push, Uber formed a partnership with United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Canada nearly a year ago.

The partnership allows UFCW Canada to provide representation to about 100,000 Canadian drivers and couriers, if requested by the workers, when they are facing account deactivations and other disputes with Uber.

Workers are not charged for the representation, which is jointly covered by Uber and UFCW Canada.

But many workers and at least one union objected to the arrangement, accusing Uber of striking the partnership to quiet UFCW, which previously had concerns about driver compensation and rights.

“This is the illusion of a union. This is the illusion of workers representation, but it is not,” Brice Sopher, a Toronto UberEats courier representing Gig Workers United, previously said.

“It is more so to give Uber the protection, the veneer of being progressive, while they will continue probably to push for the regressive rolling back of worker's rights.”

There was also opposition from the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW), which made a complaint to the Ontario Labour Relations Board.

CUPW claimed the UFCW agreement was formed without worker input, used its app and email list to promote the agreement to drivers and couriers and favoured one union over another while workers were organizing.

The matter is still before the board, but Byrne said, “UFCW doesn't speak for the whole progressive movement in Canada.”

“We absolutely respect other people's right to take shots at us and criticize and give feedback about the work that we do with UFCW and more broadly.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 10, 2023.