VANCOUVER - Researchers at the University of British Columbia have discovered what they are calling a “weak spot” in the virus that causes COVID-19, paving the way for potential new treatments effective against all strains.

A study published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature Communications says the “key vulnerability” is found in all major variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“We're always looking for, well, is there a chink in the armour? Is there a spot that is not changing so much, that we can direct antibodies to that spot?” the study's senior author, Dr. Sriram Subramaniam, said in an interview.

“That is the value of the new finding, that it tells us where to focus our attention.”

Exploiting that weakness could lead to new ways of fighting the illness that has killed almost 6.5 million people across the globe since it was identified more than two years ago, the study says.

Subramaniam, a professor in UBC's faculty of medicine, said the team had studied the virus at an atomic level to find the weak spot and identify an antibody fragment that can attach to it across the virus's many mutations, including the surging Omicron subvariants.

Antibodies counteract viruses by attaching like a key in a lock. They are naturally produced by the body to fight infection, but can also be made in a laboratory and administered to patients as a treatment, becoming less effective over time as viruses mutate.

But Subramaniam said the weak spot his team has identified is constant in all seven major variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, meaning one antibody could act as a “master key” capable of overcoming extensive mutations.

The weak spot and master key “unlock a whole new realm of treatment possibilities,” which have the potential to be effective against current or future variants of the virus that causes COVID-19, he said in a statement.

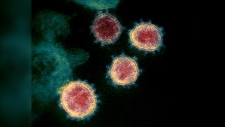

The researchers began with the knowledge that the immune system typically responds to what it sees on the surface of the virus, or the spike protein in SARS-CoV-2, he said. All viruses mutate and the concern with each new variant of COVID-19 has been whether the immune system will be able to recognize the mutated form.

“The existence of a large number of mutations made it a much more effective escape artist from our immune system,” he said.

The weak spot is located on the spike protein, he said. The antibody fragment neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by attaching to the spike protein and blocking the virus from entering human cells, he said.

“We used very advanced imaging tools to literally zero in and cast a spotlight on the interaction of the spike protein with antibodies,” he said.

The special thing about the identified antibody fragment is that it attaches next to the site where the spike protein binds with human cells instead of directly on it, he said.

“It actually puts out a couple of fingers that still block the binding,” he said. “So it achieves this effect by sitting next door.”

In some ways, it's less like locking the door than stretching an arm out to block entry, he said.

“It's an interesting physical block that sits close by, but not exactly at that site. And that may well be why (the site) has not mutated so much over time.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 18, 2022.