BAGHDAD - Pope Francis opened the first-ever papal visit to Iraq on Friday with a plea for the country to protect its centuries-old diversity, urging Muslims to embrace their Christian neighbours as a precious resource and asking the embattled Christian community -- “though small like a mustard seed” -- to persevere.

Francis brushed aside the coronavirus pandemic and security concerns to resume his globe-trotting papacy after a yearlong hiatus spent under COVID-19 lockdown in Vatican City. His primary aim over the weekend is to encourage Iraq's dwindling Christian population, which was violently persecuted by the Islamic State group and still faces discrimination by the Muslim majority, to stay and help rebuild the country devastated by wars and strife.

“Only if we learn to look beyond our differences and see each other as members of the same human family,” Francis told Iraqi authorities in his welcoming address, “will we be able to begin an effective process of rebuilding and leave to future generations a better, more just and more humane world.”

The 84-year-old pope donned a facemask during the flight from Rome and throughout all his protocol visits, as did his hosts. But the masks came off when the leaders sat down to talk, and social distancing and other health measures appeared lax at the airport and on the streets of Baghdad, despite the country's worsening COVID-19 outbreak.

The government is eager to show off the relative stability it has achieved after the defeat of the IS “caliphate.” Nonetheless, security measures were tight.

Francis, who relishes plunging into crowds and likes to travel in an open-sided popemobile, was transported around Baghdad in an armoured black BMWi750, flanked by rows of motorcycle police. It was believed to be the first time Francis had used a bulletproof car - both to protect him and keep crowds from forming.

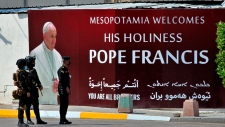

Iraqis, though, seemed keen to welcome Francis and the global attention his visit brought. Some lined the road to cheer his motorcade. Banners and posters in central Baghdad depicted Francis with the slogan “We are all Brothers.”

Some hoping to get close were sorely disappointed by the heavy security cordons.

“It was my great wish to meet the pope and pray for my sick daughter and pray for her to be healed. But this wish was not fulfilled,” said Raad William Georges, a 52-year-old father of three who said he was turned away when he tried to see Francis during his visit to Our Lady of Salvation Cathedral in the Karrada neighbourhood.

“This opportunity will not be repeated,” he said ruefully. “I will try tomorrow, I know it will not happen, but I will try.”

Francis told reporters aboard the papal plane that he was happy to be resuming his travels again and said it was particularly symbolic that his first trip was to Iraq, the traditional birthplace of Abraham, revered by Muslims, Christians and Jews.

“This is an emblematic journey,” he said. “It is also a duty to a land tormented by many years.”

Francis was visibly limping throughout the afternoon in a sign his sciatica nerve pain, which has flared and forced him to cancel events recently, was possibly bothering him. He nearly tripped as he climbed up the steps to the cathedral and an aide had to steady him.

At a pomp-filled gathering with President Barham Salih at a palace inside Baghdad's heavily fortified Green Zone, Francis said Christians and other minorities in Iraq deserve the same rights and protections as the Shiite Muslim majority.

“The religious, cultural and ethnic diversity that has been a hallmark of Iraqi society for millennia is a precious resource on which to draw, not an obstacle to eliminate,” he said. “Iraq today is called to show everyone, especially in the Middle East, that diversity, instead of giving rise to conflict, should lead to harmonious co-operation in the life of society.”

Salih, a member of Iraq's ethnic Kurdish minority, echoed his call.

“The East cannot be imagined without Christians,” Salih said. “The continued migration of Christians from the countries of the east will have dire consequences for the ability of the people from the same region to live together.”

The Iraq visit is in keeping with Francis' long-standing effort to improve relations with the Muslim world, which has accelerated in recent years with his friendship with a leading Sunni cleric, Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb. It will reach a new high with his meeting Saturday with Iraq's leading Shiite cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, a figure revered in Iraq and beyond.

In Iraq, the pontiff bringing his call for tolerance to a country rich in ethnic and religious diversity but deeply traumatized by hatreds. Since the 2003 U.S. invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein, it has seen vicious sectarian violence between Shiites and Sunni Muslims, clashes and tensions between Arabs and Kurds, and militant atrocities against minorities like Christians and Yazidis.

The few Christians who remain harbour a lingering mistrust of their Muslim neighbours and face discrimination that long predated IS.

Iraq's Christians, whose presence here goes back nearly to the time of Christ, belong to a number of rites and denominations, with the Chaldean Catholic the largest, along with Syriac Catholics, Assyrians and several Orthodox churches. They once constituted a sizeable minority in Iraq, estimated at around 1.4 million. But their numbers began to fall amid the post-2003 turmoil when Sunni militants often targeted Christians.

They received a further blow when IS in 2014 swept through northern Iraq, including traditionally Christian towns across the Nineveh plains. Their extremist version of Islam forced residents to flee to the neighbouring Kurdish region or further afield.

Few have returned - estimates suggest there are fewer than 300,000 Christians still in Iraq and many of those remain displaced from their homes. Those who did go back found homes and churches destroyed. Many feel intimidated by Shiite militias controlling some areas.

There are practical struggles, as well. Many Iraqi Christians cannot find work and blame discriminatory practices in the public sector, Iraq's largest employer. Public jobs have been mostly controlled by Shiite political elites.

For the pope, who has often travelled to places where Christians are a persecuted minority, Iraq's beleaguered Christians are the epitome of the “martyred church” that he has admired ever since he was a young Jesuit seeking to be a missionary in Asia.

At Our Lady of Salvation Cathedral, Francis prayed and honoured the victims of one of the worst massacres of Christians, the 2010 attack on the cathedral by Islamic militants that left 58 people dead.

Speaking to congregants, he urged Christians to persevere in Iraq to ensure that its Catholic community, “though small like a mustard seed, continues to enrich the life of society as a whole” - using an image found in both the Bible and Qur'an.

On Sunday, Francis will honour the dead in a Mosul square surrounded by shells of destroyed churches and meet with the small Christian community that returned to the town of Qaraqosh, where he will bless their church that was vandalized and used as a firing range by IS.

Iraq is seeing a new spike in coronavirus infections, with most new cases traced to the highly contagious variant first identified in Britain. Francis, the Vatican delegation and travelling media have been vaccinated; most Iraqis have not, raising questions about the potential for the trip to fuel infections.

The Vatican and Iraqi authorities have downplayed the threat and insisted that social distancing, crowd control and other health care measures will be enforced.

To some degree they were, but that didn't diminish the happiness of ordinary Iraqis - Christians and Muslims alike - that Francis had come to their home.

”We cannot express our joy because this for sure is a historic event which we will keep remembering,” said Rafif Issa. “All Iraqis are happy, not just the Christians. We hope it will be a blessed day for us and for all the Iraqi people.”

AP journalist Qassim Abdul-Zahra contributed.