OTTAWA - Indigenous communities and leaders across the country cheered Friday as the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the federal government's child welfare law, affirming that First Nations, Metis and Inuit have sole authority over the protection of their children.

The unanimous decision is a setback for the Quebec government, which won a victory in 2022 when the Court of Appeal found that parts of the act overstepped federal jurisdiction.

Indigenous leaders lauded the high court's findings as dozens of the very children at the heart of the decision ran rampant around an Ottawa conference room.

“Our peoples have compromised enough,” said Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador regional chief Ghislain Picard.

A group of children wearing ribbon skirts, kokum scarves and ribbon shirts sat in front of him as he spoke.

“It's time now for other governments to do the same.”

Friday's decision upholding the 2019 law ultimately affirmed that Indigenous Peoples have an inherent right to self-government that includes control over child and family services.

“The act as a whole is constitutionally valid,” the court wrote in an 110-page decision, adding that it “falls squarely within Parliament's legislative jurisdiction.”

Ottawa's law affirmed the right of Indigenous Peoples to run their own child protection services and included sections that said Indigenous legislation had the force of federal law and could supersede provincial law.

Assembly of First Nations national chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak called the decision a significant step forward, especially as First Nations have never surrendered their jurisdiction over their children and families.

“First Nations continue to have the inherent and constitutional right to care for our children and families, along with our sacred rights from Creator to raise our children surrounded by our cultures, languages, and traditions.”

The decision received multilateral support among federal political parties, with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledging the harms caused by child welfare systems, including the loss of identity, language and connection to communities.

Asked whether, if elected, he would stand by the law, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre said his party believes in “more autonomy for First Nations communities and less paternalistic control by government.”

He said the Conservatives would “respect the rights of First Nations families to raise their own children.”

The NDP's Indigenous services critic, Lori Idlout, said she hopes Quebec realizes it has an obligation to foster positive relationships with Indigenous Peoples.

Quebec's minister responsible for social services, however, said his province's fight was never with Indigenous Peoples. Instead, Lionel Carmant pointed at the federal government.

Carmant said he supports First Nations' and Inuit's exercise of greater autonomy in the area of child protection “in harmony with the Quebec system.” He added that the government would continue to analyze the decision in light of its important repercussions “on the question of the protection of vulnerable children and Indigenous governance.”

The high court ruled that nothing in the division of powers between the federal government and the provinces prevents Parliament from affirming that Indigenous Peoples' inherent right of self‑government includes legislative authority over child and family services.

“The essential matter addressed by the act involves protecting the well-being of Indigenous children, youth and families by promoting the delivery of culturally appropriate child and family services and, in so doing, advancing the process of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples,” the court wrote.

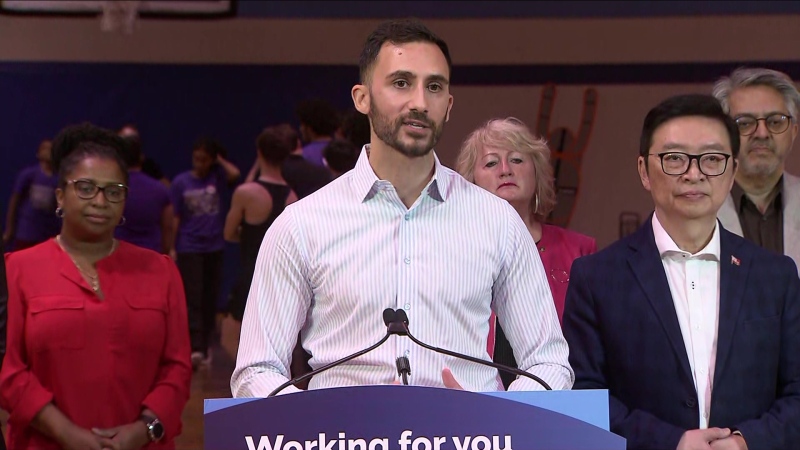

Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu said the decision paves the way for more autonomy in areas like health care and water quality, and called it “truly historic.”

Speaking alongside Hajdu and Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Gary Anandasangaree, Natan Obed said Inuit will work toward child welfare arrangements of their own.

“We will not be impeded by the demands of the provinces and territories, who would imagine that we do not have this right or are trying to put roadblocks in the way of implementing this right,” said Obed, who serves as the president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

Cassidy Caron, president of the Metis National Council, similarly said Metis look forward to entering into constructive agreements with the federal government, “and to continue down this pathway in a really good way.”

The Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations said in a statement the decision was “landmark victory” that “represents a significant step forward in recognizing First Nation jurisdiction and upholding the rights of Indigenous children and their families.”

Grand Chief Cody Thomas called it a historic moment.

The Innu Nation said that in the past few years, “Innu have been working actively towards the creation of an Innu law” for child and family services.

“Today's decision affirms that we can continue to forge ahead in the work we are doing to create our own law to protect and care for our children in a way that both honours our Innu culture and is rooted in our connection to our land.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 9, 2024.

- With files from Anja Karadeglija and Pierre Saint-Arnaud