In NFL limbo for the last five-plus months, Adrian Peterson's future with the Minnesota Vikings is still in question.

The path toward resolution of his status has been cleared, though the clash between league and the union over the personal conduct policy persists.

Commissioner Roger Goodell and the NFL were handed a second high-profile legal defeat Thursday, when U.S. District Judge David Doty overruled league arbitrator Harold Henderson's December denial of the six-time Pro Bowl running back's appeal.

Doty ruled that Henderson "failed to meet his duty" in considering Peterson's punishment, for the child abuse charge that brought national backlash for the league on the heels of the bungled handling of the assault case involving former Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice.

Doty said the league cannot retroactively apply the standards of its new, tougher personal conduct policy to an action by Peterson that occurred before the policy was in place. The league suspended Peterson through at least April 15 under the new standard, which arose from the furor over the handling of the assault involving Rice. But Doty said in his 16-page ruling that Henderson "simply disregarded the law of the shop and in doing so failed to meet his duty" under the collective bargaining agreement.

NFL Players Association executive director DeMaurice Smith said in a statement Doty's decision was a "victory for the rule of law, due process and fairness."

The NFL promptly filed its protest to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals. The league also returned Peterson to the exempt list he spent two months on last season pending completion of the process. The NFL also said further arbitration proceedings in front of Henderson could be held before an appeal is heard by the 8th Circuit.

"Judge Doty's order did not contain any determinations concerning the fairness of the appeals process under the CBA, including the commissioner's longstanding authority to appoint a designee to act as hearing officer," NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy said. "Even so, we believe strongly that Judge Doty's order is incorrect and fundamentally at odds with well-established legal precedent governing the district court's role in reviewing arbitration decisions."

The Vikings chimed in a little later with moral support of Peterson, whom they have heaped praise on in recent weeks in obvious attempt to either welcome him back or enhance his trade value.

"Adrian Peterson is an important member of the Minnesota Vikings, and our focus remains on welcoming him back when he is able to rejoin our organization," the Vikings said. "Today's ruling leaves Adrian's status under the control of the NFL, the NFLPA and the legal system, and we will have no further comment at this time."

Peterson's return to the exempt list was just as critical of a development in this saga as was Doty's ruling. Being on the exempt list means the Vikings can now have direct contact with Peterson, which they couldn't while the suspension was in effect. Also, when the market opens March 10, they'd be allowed to trade him if they wanted. They could release him or try to restructure his contract at any time.

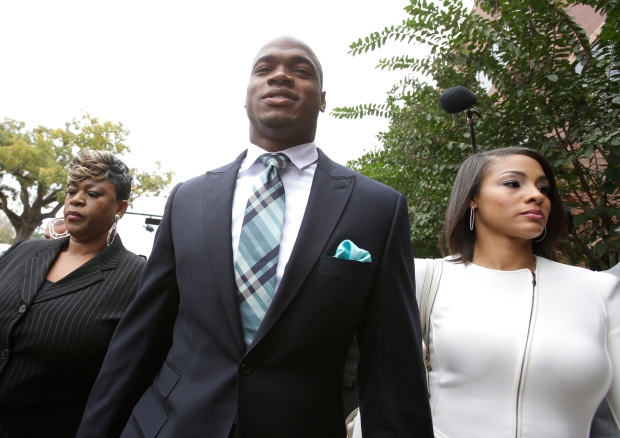

Peterson's existing deal is through 2017, carrying a $15.4 million salary cap hit for 2015. If the Vikings cut him, they'd owe him no more money and take only a $2.4 million hit to their salary cap. Peterson has no contractual leverage, but he has expressed uneasiness about returning to the only team he's ever played for. He told ESPN in a recent interview that he felt betrayed by some members of the organization during the process in which Goodell placed him on the exempt list, essentially paid leave, while the child-abuse case played out in court in Texas.

In the Rice case, Goodell changed a two-game ban to an indefinite suspension. But the arbitrator in Rice's appeal, former U.S. District Judge Barbara Jones, ruled that decision was "arbitrary" and an "abuse of discretion." Rice was seen on surveillance video knocking out the woman who's now his wife with a punch in an elevator.

The NFL argued that the ruling by Jones was irrelevant to the Peterson case, but Doty disagreed.

"The court finds no valid basis to distinguish this case from the Rice matter," he said.

The injuries to Peterson's son, delivered by a wooden switch that Peterson was using for discipline, occurred in May. Goodell's announcement of the enhanced policy came in August. The NFLPA argued the league could not retroactively apply the new policy, which increased a suspension for players involved with domestic violence from two games to six games.

"Our collective bargaining agreement has rules for implementation of the personal conduct policy and when those rules are violated, our union always stands up to protect our players' rights," Smith said. "This is yet another example why neutral arbitration is good for our players, good for the owners and good for our game."

Doty said Henderson erred in purporting to rely on factual differences in the cases of Rice and Peterson yet failing to "explain why the well-recognized bar against retroactivity did not apply to Peterson." The Rice decision aside, Doty said, Goodell should have understood his duty to only apply the new policy moving forward.

Doty's courtroom has long been a ground zero of sorts for NFL labour matters, and his ruling pattern has favoured the union more often than not.

Still, his latest rebuke of the NFL came as a surprise because it defied a collectively bargained arbitration process.

"There's no doubt that generally speaking judges don't like to overturn decisions of arbitrators," said Thomas Wassel, a labour and employment attorney and partner at Cullen and Dykman in New York.

"That's a general principle in all of labour law. ... Unless the court ruled the arbitrator clearly exceeded his authority legally or was biased in some way, even if the judge disagrees with the decision, they're not supposed to overrule the arbitrator."