In early April 2021, Filip Zahradka did all the right things. He stayed home, worked from home, only venturing out to buy groceries or run errands for his two children.

But amid a troubling wave of infection seen that month, and with the vaccine rollout still in first gear, he got sick.

On April 6, he tested positive for COVID-19. His kids did too. His breathing became laboured and difficult.

“They all got COVID and I think that they missed that he was getting worse,” his mother, Anna says.

On April 15, he went to Credit Valley Hospital in Mississauga and was admitted immediately.

More than 7,800 people have required ICU admission due to COVID-19 in Ontario since March 2020, according to federal statistics.

At least 1,992 of them died in hospital.

Filip was almost one of them.

“He went into a coma, they had to paralyze him because he got sepsis in his blood,” Anna said.

Two months after he was first admitted to Credit Valley with bilateral pneumonia due to COVID-19, his situation became dire.

He was at another hospital – Joseph Brant in Burlington – when Anna got a solemn call.

“He was not waking up - they were saying that’s it. We came and said our goodbyes,” Anna said.

But she and other family members requested a few days to think about whether to end life support.

“I got a phone call the next day,” Anna said. “He started to wake up. It’s as if he heard me.”

With sputtering vaccine deliveries from the federal government, the soonest Filip would have been eligible for a first shot of a vaccine would be the end of April.

By then, Filip was already sedated, breathing through a tube.

Filip stayed in a hospital bed until October 2021, when he was transferred to the Moir Centre for Complex Continuing Care in Mississauga, almost completely unable to move, or speak.

He worked on his speech with a therapist and programs on a tablet.

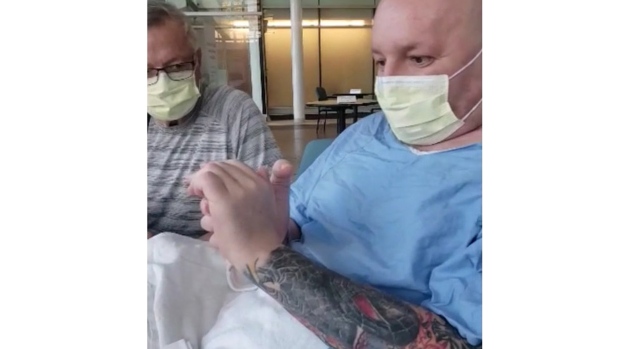

Therapists there massage his limbs, and work on pushing through minor movements of one of his hands, or his legs.

“The improvement goes very slow,” Anna said. “We did so much exercise with him, his hands, his legs. So far, his right hand is better than his left.”

It’s tiresome for everyone involved, with the smallest changes having to serve as markers of improvement.

“He lifts his head, but we don’t sit him up,” Anna explained. “We sit him up at the side of the bed so he can support himself with the side of the bed.”

But he needs more.

“The system is lacking a place where he could go, where someone could help him,” Anna said.

“They don’t want me to stay here,” Filip told CP24 in February. “So my mom sent out a video of me with long-haul COVID,” he said.

One of the sites they applied to with the video was the Bickle Centre at Toronto Rehab Hospital.

“They’re the only ones that wanted to see me,” Filip said.

In early March, the Bickle Centre said it would admit Filip for comprehensive rehabilitation, but he would need to get a motorized electric wheelchair, something he only successfully secured with government aid.

Dr. Mark Bayley of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, which oversees the Bickle Centre in Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood, says they are seeing more and more newly admitted patients like Filip, especially since about the time Filip became sick.

“The first and second wave (patients) were older, they were folks with previous medical conditions but after Delta and Omicron, we are now seeing people in 30s and 40s who were really, really healthy.”

Bayley said that prior to COVID, they’d occasionally get someone who became very ill from influenza, and required the same sort of intense, multi-system help to get back on their feet and into their normal lives again.

But now they’re helping 15 to 20 people at a time, and the ones being discharged from hospital post-Omicron are just starting to arrive at Bickle.

The facilities offering complex care and rehabilitation needs in Ontario will likely need more funding and capacity because of the disabling potential of severe COVID-19.

“For the next couple of years there’s going to be a long tail of people like the individual you’re aware of, that’s going to take many months or years to recover,” Bayley said.

A guidance document published in Dec. 2021 by Ontario Health estimated up to 80,000 people were suffering post-COVID or long-haul COVID-19 symptoms, defined as someone suffering one or more COVID-19 symptoms for more than four weeks after infection.

While only a small fraction of those tens of thousands are in Filip’s situation, the influx is clearly straining Ontario’s complex care facilities.

Anna said he and Filip were refused admission to several centres to continue Filip’s recovery, simply because they did not have enough space.

It prompted Anna to circulate a petition, calling on the province to build more space with long-COVID sufferers with complex needs.

Asked if they plan to increase size and capacity of such facilities, a spokesperson for Ontario’s Ministry of Health, W.D. Lighthall, told CP24 that for now, hospitals can fund expansion of these programs through their existing budgets.

“In working with Ontario Health, hospitals can fund services in their areas, such as dedicated post COVID-19 clinics, through their global budgets.”

They identified eight centres or clinics specifically meant for long-haul COVID sufferers already in operation in Ontario, with most of them offering only dedicated outpatient services at this time.

“The ministry, in partnership with stakeholders, is working to further understand the scope, scale, and impacts of this disease, and explore options for responsive, evidence-based management and treatment,” Lighthall said. “This includes consideration of approaches taken and lessons learned in other jurisdictions.”

Preparing for his transfer, Anna filmed Filip taking his wheelchair for its first spin in the hallways at Moir in Mississauga.

“He’s happier, he’s smiling, he loves riding it,” she said.

While he works on building his mobility, there’s also the question of his finances.

He had short-term disability from his job, “but that’s gone now,” he says.

He’s since secured Canada Pension Plan disability payments, and is still waiting to see if he will be accepted into the Ontario Disability Support Program.

His children, aged 11 and 14, have had to connect with him sometimes only over the phone, Zoom and Facetime, either because Filip’s wing at the hospital or Moir was in outbreak, or they were sick with COVID-19 acquired from school.

“They want me to come home,” Filip said, his speaking slow and laboured, but determined, relying upon months of rehabilitation and speech pathology efforts to get him moving and expressing himself again.

“I miss it. My life was normal, completely normal. Since then it turned upside down.”