DURBAN, South Africa - Some ministers and top climate negotiators left Durban without an agreement Saturday, with time running out and the prospect of an inconclusive end jeopardizing new momentum in the fight against global warming.

Negotiators from 194 nations had worked straight through Thursday and Friday night. Nearly 24 hours after the two-week-long talks were to have wrapped up Friday, delegates appeared stuck on issues related to the next phase of fighting climate change. An indecisive outcome will be an embarrassment to South Africa, hosting the U.N. climate talks for the first time.

If no decision is reached for lack of time, an additional midyear conference could be called to complete the agenda, or government ministers could meet on the sidelines of a major environmental summit in Brazil next May.

Chief among the unresolved differences was a clause encouraging countries to pledge greater reductions of greenhouse gases and to close what is known as the emissions gap. More than 80 countries have made either legally binding or voluntary pledges to control carbon emissions. But taken together, they will not go far enough to avert a potentially catastrophic rise in average temperatures this century, according to scientific modeling and projections.

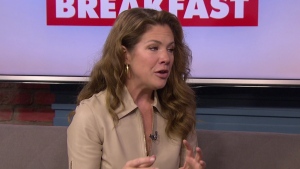

European Commissioner Connie Hedegaard said a lack of ambition could derail progress made on a host of other issues.

Countries had made concessions that they had resisted for years, and it would be "irresponsible" to lose that momentum now, she said.

"We are working to the very last minute to secure that we cash in what has been achieved and what should be achieved here," she told The Associated Press.

Strong language on curbing emissions is of prime importance to small islands endangered by rising ocean levels and by many poor countries who live in extreme conditions that will be worsened by global warming.

These island states and poorest countries lined up behind an EU plan to begin talks on a future agreement that would come into effect no later than 2020.

As negotiations progressed, the United States and India eased their objections to compromises. But China remained a strong holdout, EU officials said on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the continuing talks.

Under discussion was an extension of binding pledges by the EU and a few other industrial countries to cut carbon emissions under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the only treaty governing global warming. Those commitments expire next year.

The EU, the primary bloc bound by commitments under Kyoto, said an extension was possible, on the condition that new talks would start on an accord to succeed Kyoto. The talks would conclude by 2015, allowing five years for it to be ratified by national legislatures. The plan insists the new agreement equally oblige all countries -- not just the few industrial powers -- to abide by emission targets.

Developing countries are adamant that the Kyoto commitments continue since it is the only agreement that compels any nation to reduce emissions. Industrial countries say the document is deeply flawed because it makes no demands on heavily polluting developing countries. It was for that reason that the U.S. never ratified it.

But for the first time developing countries were talking about accepting legally binding targets on their own emissions, "and that's a very big deal," said Samantha Smith, of WWF International. "That reflects a major macroeconomic and geopolitical change" in climate negotiations.

Host country South Africa organized the final stages of negotiations into "indabas," a Zulu word meaning important meetings that carry the weight of a rich African culture.

At the indaba, the chief delegate from fewer than 30 countries, each with one aide, sat around an oblong table to thrash over text. Dozens of delegates were allowed to stand and observe but not to participate.

After the first meeting that ran overnight into Friday morning, conference president Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, who is South Africa's foreign minister, drafted an eight-point compromise on the key question of the legal form of a post-2020 regime. The wording would imply how tightly countries would be held accountable for their emissions.

But the text was too soft for the Europeans and for the most vulnerable countries threatened by rising oceans, more frequent droughts and fiercer storms.

With passion rarely heard in a negotiating room, countries like Barbados pleaded for language instructing all parties to dig deeper into their carbon emissions and to speed up the process, arguing that the survival of their countries and millions of climate-stressed people were at risk.

Nkoana-Mashabane drafted new text after midnight Saturday that largely answered those criticisms. The U.S. told the indaba it could live with the language, but the reactions of China and India were not clear.